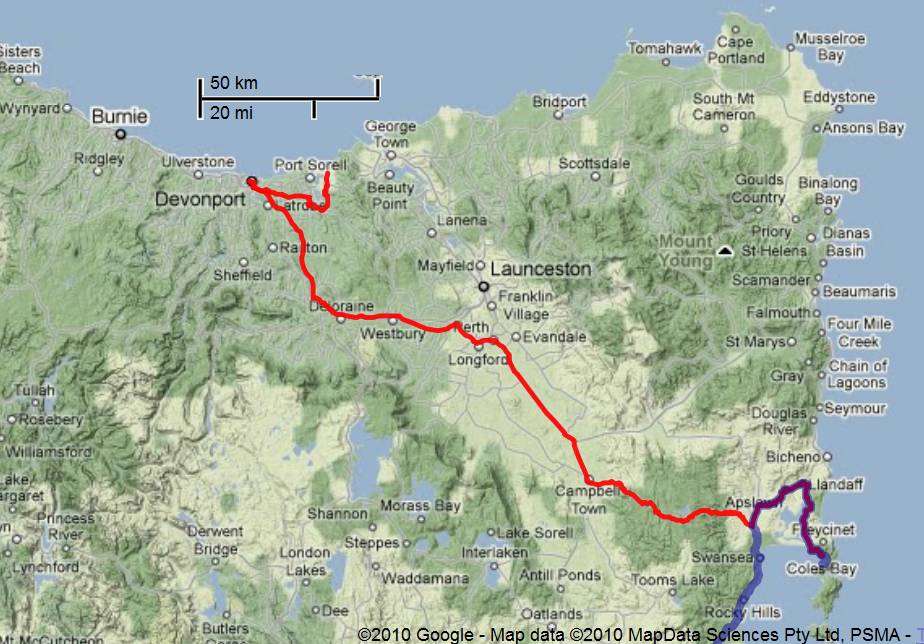

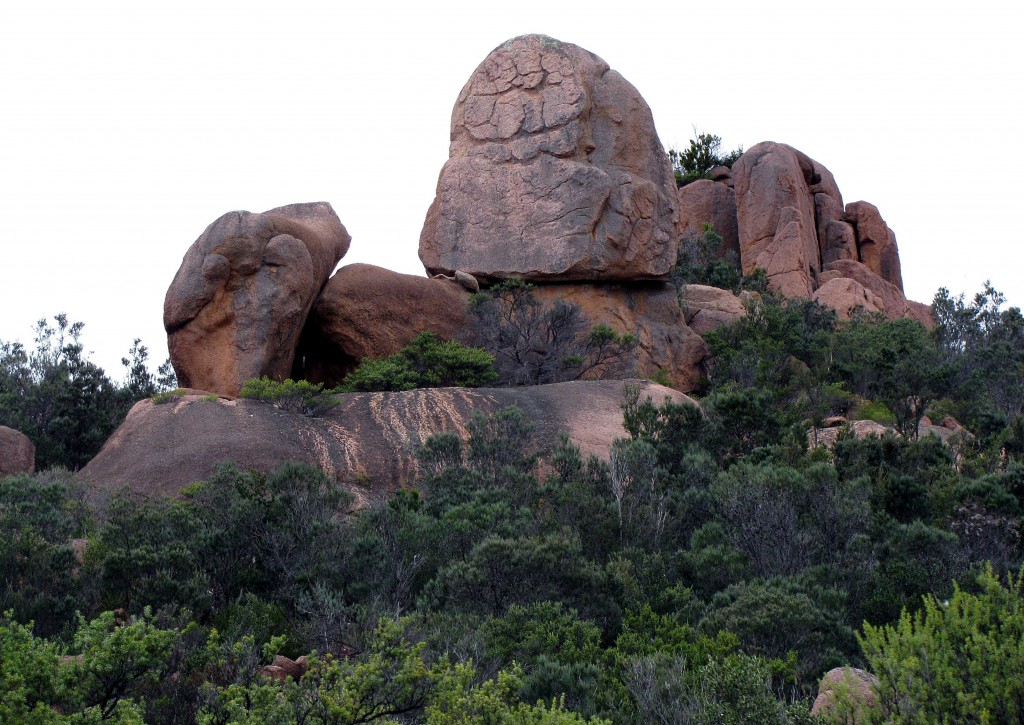

Pink Granite Formations Above Wineglass Bay (© Vilis Nams)

Under a dull sky promising rain, Vilis and I broke camp at Richardson’s Beach and drove to the trailhead of the Wineglass Bay Track, which is also the start of the Wineglass Bay/Hazards Circuit. According to our guidebook, the climb to the Wineglass Bay lookout has become a tourist pilgrimage.1 During January, more than 500 visitors climb the 300-plus steps each day to view what’s considered one of the world’s most beautiful beaches.2 Vilis and I hoped significantly fewer visitors would be on the trail today.

Track to Wineglass Bay (© Vilis Nams)

The squawks of a little wattlebird and forest raven accompanied us as we headed off on a beautifully-maintained track no doubt kept up to snuff for all the pilgrims. The trail was edged with pink granite stones, and enormous boulders loomed over it like a giant’s building blocks and marbles. We climbed staircases of granite steps interspersed with flat track and passed a curving, rolling bench that was designed by an architecture class and echoed the sweeping curves of the landscape.

On the Steps to Wineglass Bay (© Vilis Nams) (Hiked up, not down.)

Bench on Wineglass Bay Track (© Vilis Nams)

From the lookout (330 steps up and 32 down), our view spanned the rugged, bush-covered hills of the lower Forestier Peninsula, the rocky finger of Cape Forestier jutting out to Lemon Rock and the Tasman Sea, and the pale, symmetrical beach of Wineglass Bay. We spotted sailboats anchored on the blue water of the bay that once ran red from the blood of whales butchered on the shore. It was that bloodied water that gave the bay its name, as if it were a goblet filled with red wine.3

Prior to the arrival of the whalers in the early 1800’s, sealers (one of whom was the African-American sealing captain Richard “Black” Hazard, after whom the granite peaks of The Hazards and Hazard Beach are named) had slaughtered coastal seal colonies following the European settlement of Tasmania.4 Even earlier, the Toorernomairremener Aboriginal people had made seasonal forays to the east coast from the Midlands in the interior in order to harvest oysters and hunt seals.4

Wineglass Bay (© Vilis Nams)

Leaving the lookout, we continued along on the rest of the 11-kilometre Wineglass Bay/Hazards Beach Circuit, the remainder of the loop trail leading down to Wineglass Bay, across an isthmus separating Wineglass Bay from Promise Bay, and then along Hazards Beach and around a rocky headland back to the Wineglass Bay trailhead. On the first section of track, we descended a rugged but well-used path having less-decorative granite steps and wood log steps interspersed with stretches of sand. En route to Wineglass Bay, it led us through boulder fields, past massive outcrops of pink granite fractured into irregular blocks (see photo at start of post), and through open forest having a sparse understory of grasses and ferns.

At the shoreline, wind-twisted shrubs and she-oaks dominated the vegetation. Grey-green waves rolled sand in their depths and pounded onto a sharply-inclined beach. While walking half the beach’s length, Vilis and I observed a little pied cormorant that was bathing in the waves one moment and slammed onto the beach by a wall of water in the next. Stranded upside down on the sand, the bird kicked wildly to right itself before floating back out to sea on another wave.

Wineglass Bay Beach, with The Hazards in the Background (© Vilis Nams)

Isthmus Track (© Vilis Nams)

After retracing our steps along the beach, we hiked the Isthmus Track to Hazards Beach through open, stunted woodland with an understory of ferns, grasses, and shrubs. Vilis spotted a red-necked wallaby feeding on grasses near a trickling stream, its rusty neck obvious, its delicate black forefeet held against its chest. We observed several more wallabies near the trail, a couple of them feeding on the branchlets of she-oak. Animal trails were visible crossing the track, and we encountered piles of cube-like scats on the track. “What would make dung like that?” Vilis asked, to which I replied, “Wombats, maybe.” From our park map, we saw that the Isthmus Track passed close to a body of fresh water, which likely explained the abundance of wildlife and sign near the trail.

Red-necked Wallaby (© Vilis Nams)

Find the Wallabies (© Vilis Nams)

We hiked from the open forest through sandy scrubland and onto Hazards Beach, passing two runners along the trail and another, younger runner slogging through sand on a ridge above the beach. They were the first humans we’d encountered. A blasting wind blew bits of dried seaweed down the beach ahead of us as we followed the hard-packed sand for a kilometre before climbing a set of wood-slat steps leading into thick, dark she-oak woods.

Vilis on Slat Steps, Hazards Beach Track (© Magi Nams)

In the woods, which were barren of understory plants, we noted scattered oyster shells and walked past piles of shells that I later learned from a park interpretive sign were food scrap middens of the Toorernomairremener peope, who camped in the area and harvested seafood from the ocean over a period of thousands of years.

Shell Midden (© Vilis Nams)

Cove, Hazards Beach Track (© Vilis Nams)

The weather toyed with sunshine and rain, causing us to juggle clothing as we alternately hiked across outcrops of pink granite bedrock slanting down to the sea and stretches of soft, grey sand worn deep by human feet. The trail led us around Fleurieu Point and north past numerous small, rocky coves toward the trailhead. Glacial erratics – enormous boulders stranded after the retreat of glaciers – littered the landscape and created artistic jumbles of pink granite.

Glacial Erratics (© Vilis Nams)

As we neared the trailhead, we hiked through open woodland having short, wind-sculpted trees and an understory of heaths and grass-trees, some of which were dead. An interpretive sign informed us that a disease called phytophthora root rot, which is easily spread by bushwalkers carrying mud from one area to another, was attacking the heaths, grass-trees, bush peas, and black peppermint trees in the park. The sign advised us to clean soil from our shoes and tent pegs to limit spread of the disease.

Healthy Grass-tree (© Vilis Nams)

Dead Grass-tree (© Vilis Nams)

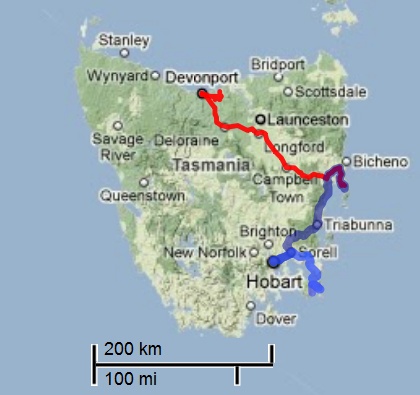

Four and a half hours after setting out on the circuit, we returned to the trailhead. After a quick picnic lunch at windy Honeymoon Bay, we backtracked out of Freycinet National Park, aiming for our next destination 300 kilometres away – Narawntapu National Park on the north coast of Tasmania. Heading inland on the B34, we angled northwest through a wide plain and up into forested hills and tawny rangeland speckled with eucalypts and shrubs. Storm clouds billowed overhead as we crossed over a saddle into the Northern Midlands, a collage of pastoral and forested land.

Northern Midlands of Tasmania (© Magi Nams)

Campbell Town looked dry, and beyond it, the uplands of the Great Western Tiers, veiled by cloud and curtains of showers, reared above an inland plain touched with the colours of autumn. To me, that plain, with its cropfields, hayland, sheep, and black Angus cattle, looked like the heartland of Tasmania.

From Perth, we traveled west past Deloraine, with its rolling hills and lusher, greener landscape, and then north to Devonport on the Bass Strait. There, we replenished our food supplies before driving east and north to Narawntapu National Park, the supposed ‘Serengeti of Tasmania.’5 We selected a campsite at Baker’s Point and erected our tent under the sheltering boughs of a copse of she-oaks.

Common Wombat in Nest on Plain at Narawntapu National Park (© Vilis Nams)

After hurryng through another meal, we drove to the open plain at the Springlawn Campground just before sunset. In the last of the sunlight, we spotted mobs of wallabies and eastern grey kangaroos feeding on plains of heavily-grazed grasses. Vilis spotted a large, dark, chunky animal that could only be a common wombat grazing on its own. Feeling the thrill of excitement, we crept closer to the wombat, discovering three wombat burrows (one in sandy soil beneath a clump of shrubs and the others on the open plain) and plenty of wombat and macropod droppings. Vilis photographed the wombat, which was obviously habituated to humans, and we watched it dig in the soil and in a mound of dead ferns and grasses that resembled a strawpile. We were both struck by its similarity to a koala, particularly in its face and the way it moved, swinging its legs in a pigeon-toed gait.

Common Wombat (© Vilis Nams)

As dusk crept toward darkness, we noticed more wombats on the plain and were able to approach a younger, smaller animal so closely we could hear its teeth snipping off grass blades. We saw no Tasmanian devils, though, not on the plain nor along the roadsides when we drove back to our campsite in darkness, startling macropods into bounding into fields of fern bordering the road.

Chilled deeply by a bitterly cold wind blowing in off Bass Strait, we crawled into our sleeping bags and snuggled down while stars and a crescent moon lit the night above us.

Today’s fauna: forest raven, little wattlebirds, pied cormorant, laughing kookaburras, superb fairy-wren *common wombats, red-necked wallabies, rufous-bellied pademelons, eastern grey kangaroos. (* lifelist sighting) Also macropod scats and common wombat burrows, diggings, straw piles, and scats.

References:

1. James Stewart and Margo Daly. 2008. The Rough Guide to Tasmania. Rough Guides. New York. p. 186; 2. Ibid. p. 192; 3. Ibid. p. 188; 4. Ibid. p. 188; 5. Ibid. p. 261.