Kalkani Crater Trailhead (© Magi Nams)

After an early morning encore visit to Hundred Mile Swamp – the wetland alive with bird song and macropods, yet serene – we devoted the remainder of the day to Undara’s volcanic features. A short drive into the national park led us to the base of Kalkani Volcano and its crater rim circuit track. We hiked up a gently-graded 600-metre path to the crater’s rim, passing through stunted woodland, some of which had been recently scorched by fire. After the abundant bird song of the swamp, the open woodland was strikingly quiet, its silence broken only by wind rustling leaves and a few avian vocalizations – the shrill notes of a couple weebills and a single, subdued currawong bell tone.

From the crater’s rim, we looked out over savannah woodland stretching for hundreds, perhaps thousands of kilometres. In a bushwalk unlike any other we’ve done in Australia, we hiked the crater’s rim with stunted, tortured-looking trees alongside us and volcanic rubble beneath our feet – some of it ground into gravel and sand.

Here I’m beside Kalkani Circuit Track (© Vilis Nams)

Vilis and Kalkani Scoria (© Magi Nams)

From various vantage points, we gazed down into the crater, its gentle slopes and depression vegetated with grasses and scattered trees. A flattened central ‘plain’ looked as though it might hold water in the wet season. Kalkani Volcano erupted between 190,000 and 400,000 years ago, spewing a molten froth of gas-filled lava over the landscape.1 The ejected magma cooled while falling and piled up as a cone of bubble-riddled rock called scoria. Other scoria peaks – Rangaranga Hill and Commissioner’s Cap – were visible from Kalkani’s rim, thrusting their sharply pointed peaks into the sky. Yesterday and this morning, Vilis and I encountered long piles of black, bubble-riddled rocks at Hundred Mile Swamp, testimony to the volcanic history of the area. The most recent volcanic eruptions occurred only 20,000 years ago2, long after Aboriginal peoples had settled the continent.

Although the vegetation of the crater rim was primarily eucalypt woodland, a small pocket of semi-evergreen vine thicket, a type of dry rainforest, cloaked one area, its dense thickets of trees and vines noticeably different from the sparsely-treed gum woodland. Since grass doesn’t grow on the rocks where the vine thicket grows, fires are unable to invade the thicket, enabling it to survive.1 When we looked out over the vast expanses of savannah woodland, we were able to discern lines of darker, lusher green that indicated the presence of vine thickets, thought to be remnants from the past when the climate was wetter in this area.1 The thickets now grow primarily in sections of collapsed lava tubes that originated from the Undara Volcanic eruption.

View from Kalkani Volcano Crater Rim (© Vilis Nams)

Inside Stevenson’s Tube (© Vilis Nams)

Unlike Kalkani, Undara Volcano’s eruption was not an explosive fountain of gas-filled magma. Being a shield volcano created by a moving apart of the plates of the earth’s crust, its eruption sent streams of lava pouring over the landscape to the north, west, and east of the volcano,3 which is located 12 kilometres southeast of Kalkani. That eruption occurred 190,000 years ago, after Kalkani’s, and sent lava down streambeds and creekbeds as far as 160 kilometres from Undara.3 (The Aboriginal word ‘undara’ means ‘long way.’4) The lava on the exterior of the streams of molten rock cooled and solidified more quickly than the liquid interior which continued to flow, forming a series of long lava tubes that are now protected within the national park.

In mid-afternoon, Vilis and I joined a tour to the Undara Lava Tubes. After a short drive through open gum woodland, we descended stairs into a rocky gully formed long ago by the collapse of a lava tube roof and now vegetated with semi-evergreen vine thicket and inhabited by Mareeba rock wallabies (“Look for rocks with ears,” our guide instructed). Beyond the gully lay the gaping mouth of Stevenson Tube, warm, humid, and smelling of bat guano. With our path lit by the light of our guide’s torch, we followed stairs and a boardwalk into the relatively short tube blocked by a rock wall at its far end, pausing to view eastern horseshoe bats roosting on the tube ceiling, tree roots dangling down into the tube, and the rock formations of the tube. Smooth lava flow lines were evident at the base of the tube wall, as were, in some places, individual lava rocks jammed together and composing the roof of the tube. It was easy to see how thin sections of lava tube roofs with unstable rocks could collapse and form gullies like the one outside the tube.

Rock Wall Reflections in Stevenson’s Tube (© Vilis Nams)

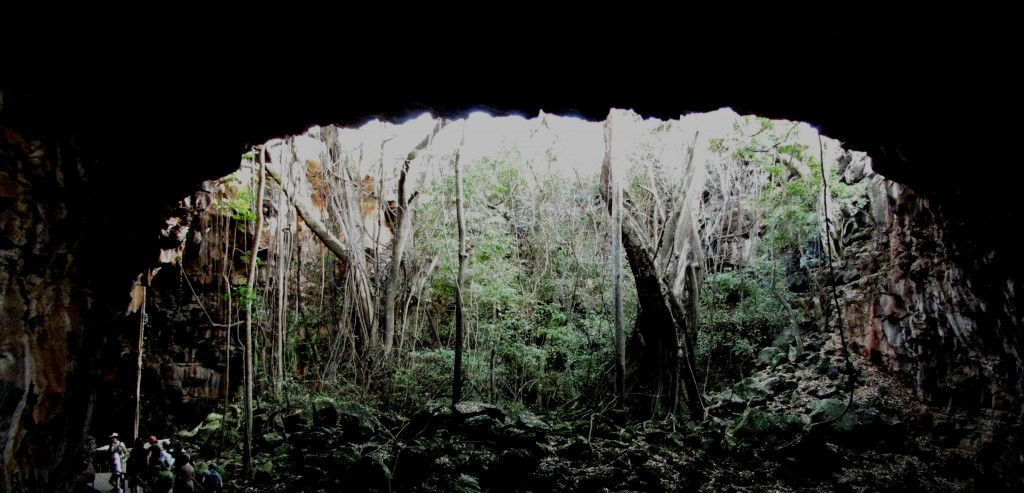

After exiting the blocked tube, we followed more boardwalk through the gully and through sections of tube open at both ends and refreshingly cool within. The sheer sizes of the tubes presented mind-boggling evidence of the volume of lava that had flowed from Undara Volcano. Seen from within a lava tube, the arched entrance and lush vegetation beyond appeared like a vision of the richness of life on the earth. When we climbed stairs up out of the gully and walked through the savannah woodland, it seemed an almost surreal thought that cavernous tubes with walls of lava lay beneath our feet.

Undara Lava Tube Archway (© Vilis Nams)

Magpie-lark and Macropods at Hundred Mile Swamp (© Vilis Nams)

Today’s birds and other fauna: pied currawongs, rainbow lorikeets, laughing kookaburras, *apostlebirds, Australian raven, Australian magpies, little friarbirds, red-winged parrots, straw-necked ibises, magpie-larks, masked lapwings, white-faced herons, great egrets, Pacific black ducks, *grey teal, Australian wood ducks, Torresian crow, peaceful dove, forest kingfisher, willie wagtails, *squatter pigeons, pied butcherbird, noisy friarbirds, brown honeyeater, pale-headed rosellas, *weebills, white-bellied cuckoo-shrike, *black wallabies, *common wallaroos (euros), *Mareeba rock wallabies, eastern grey kangaroos, *eastern horseshoe bats, *zigzag velvet geckos. (*denotes lifelist sighting)

References:

1. Queensland Government, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. Spewing explosions of scoria. Interpretive sign atop Kalkani Volcano.

2. Queensland Government, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. Kalkani crater rim walk. Interpretive sign at base of Kalkani Volcano.

3. Queensland Government, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service. Welcome to Undara Volcanic National Park. Interpretive sign at base of Kalkani Volcano.

4. Queensland Government, Environment and Resources Management. Undara Volcanic National Park, About. Updated 30-Apr-2010. Accessed 22-Jul-2010. http://www.derm.qld.gov.au/parks/undara-volcanic/about.html