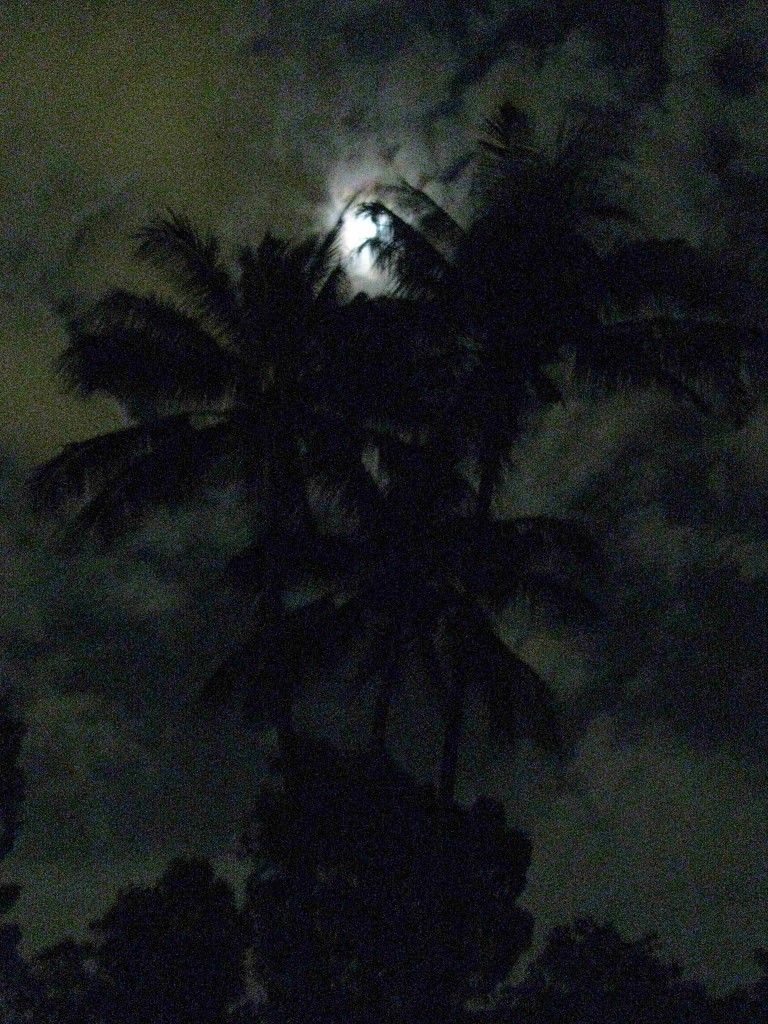

At 6:40 p.m., Vilis and I changed our clothes to go out on the town, hunting nightlife. We pulled on long pants and long-sleeved shirts and tucked flashlights into our pockets. A duet of barking owls serenaded the suburb of Rosslea as we prepared to leave the house. A a half-moon veiled by cloud greeted us at the door of the golf course ‘nightclub.’ A warm, sweet breeze carried the light rhythms of crickets and other insects harmonizing with the night.

Coconut Palms and Moon (©Vilis Nams)

Creeping along the edge of the golf course, we listened for rustlings in tree foliage and looked for movements in the grass or on the path. On Monday evening, while strolling past the golf course, we had spotted a distinctly mammalian shape on a tree branch. The shape had, quite amazingly, crept down the branch to a main trunk a half dozen feet away from us, granting us a good view of its pointed face, hunched body, and long, short-haired tail curled into a half-ring as it hung down. It was that nocturnal critter – which we, after perusing the possibilities in my mammal guide, decided may have been a common ringtail possum – that inspired this evening’s hunt for more of Townsville’s natural nightlife.

We slipped quietly onto the golf course, scanning the lawns for movement and flicking our flashlights on to peer into the canopies of trees from beneath. In the Centenary Gardens, a banyan fig loomed above and around us like some fortress patrolled by moths and by other critters that rustled leaves on the ground, but eluded our flashlight beams. Coconut palms on the open swales of the course swept up into a cloud-curdled sky. The weather towers on Mount Stuart, lit by red lights, appeared to hover threateningly above the earth, with the granite peak supporting them invisible in the purple-grey city darkness.

Asleep for the Night (©Vilis Nams)

Clicks and buzzes of insects assailed our ears, as did the wails of bush stone-curlews and squabblings of feeding bats. A pungent plant smell drifted into our nostrils. The golf course, with its mowed lawns and cropped greens, offered easy walking that enabled us to focus on our search for nocturnal wildlife. I wondered where the abundance of birds so active diurnally on the course and at its edges spent the night. My question was soon answered by a trio of sightings of dozing birds that we caught in our flashlight beams. Two of the birds were blue-faced honeyeaters resting next to each other, another may have been a yellow-throated miner, and the other was a small bird unfamilliar to me – at least from below (I now think it may have been a brown honeyeater). This last bird, we could have reached out and seized, as it paid absolutely no heed to us. The miner shuffled restlessly on its perch, and the honeyeaters shifted about before flying to a new perch.

Cane Toad (©Vilis Nams)

Near the sewage pond, a cane toad hopped across the lawn, and two common brushtail possums scrambled up into a coconut palm, their eyes reflecting red, their long tails hanging like thick, black bottlebrushes. A number of green coconuts lay at the base of the tree, with most of them showing signs of chewing. This led me to wonder if the possums had been feeding on the coconuts before I startled them.

For nearly two hours, we explored the ‘nightclub’ of the golf course. We giggled in the warm air, gasped with surprise and delight at our discoveries, and lay on the turf to gaze up into the sky with its palm silhouettes, its curdled clouds, and its stars. We weren’t fifteen-year-old Peter Nicholson crawling down wombat burrows,1 but it’s never too late to take a night walk on the wild side.

(See my March 31 post on wombats, http://maginams.ca//2010/03/31/)

Reference:

1. James Woodford. The Secret Life of Wombats. 2001. The Text Publishing Company, Melbourne. Chapter 1: Wombat Boy, pp. 1-13.