In Sarah Murgatroyd’s book The Dig Tree: The Story of Burke & Wills1, a black-and-white photograph taken around 1911 shows the sprawling trunks of a coolibah tree. A section of the tree’s furrowed bark is peeled away in a triangular area of smooth wood overgrown at its edges by encroaching bark. Within the smooth triangle, a horizontal arrow is clearly distinguishable, and above it, the letters D-I-G. The D is less clear, partly obscured by bark, but leaves no doubt that the carved word is DIG.

The two following pages in the book illustrate a map of Australia dissected into two portions by a black, more or less vertical line that proceeds strongly northward from Melbourne, scoops out a curve to the west about half-way up the continent, and then proceeds north to near where the Flinders River empties into the Gulf of Carpentaria. At the west end of the westward scoop is a dot labelled ‘Dig Tree.’ The black line is labelled ‘Burke and Wills Route.’ A dot at the top of the black line is labelled ‘Camp 119.’

So, who were Burke and Wills, and what’s the significance of the Dig Tree?

In mid-March, while in Melbourne, Vilis and I spent a couple of hours in the National Gallery of Victoria, where we were both moved by John Longstaff’s wall-sized painting titled Arrival of Burke, Wills, and King at the deserted camp at Cooper’s Creek, Sunday evening, 21st April 1861. The painting, rendered in dull shades of brown, grey, red ochre, and black exuded devastating gloom and hopelessness. It portrayed three men in tattered clothing, one prostrate on the ground, one seated with his head hanging, and one on his feet, staring straight at the viewer, his arms limp by his sides. Two camels rested in the background lit by a full moon. A spade was visible, as was a tree carved with three rows of letters and numbers spelling DIG, 3FTW, AP21.

In the mid-1800’s, nearly two-thirds of Australia, although well and truly known to Aboriginal peoples, had not yet been explored by Europeans.2 In 1859, a diminutive Scotsman, John McDouall Stuart, for whom “only the desert was more enticing than the whiskey bottle”3 made an exploratory expedition out of South Australia into the centre of the continent, where he found pockets of prime grazing country and a potential route that could be used to bring an overland telegraph service from the north coast to Adelaide on the south coast.4

The state of Victoria, loathe to be outdone in anything by South Australia, determined to mount its own exploratory expedition, which it named the Victorian Exploring Expedition, and which departed from Melbourne amid much fanfare and confusion on August 20, 1860.5 The expedition, carrying 20 tonnes of equipment in wagons and packed on camels and horses, was headed up by Robert O’Hara Burke, a man chosen as leader by the exploration committee not because of his experience as an explorer or bushman, but because he came from a well-bred family and was courageous enough to tackle the monumental task of crossing the unknown and arid interior of the continent.6 In fact, Burke, an Irishman who had served in the Austrian military and as a police superintendent in Victoria after immigrating to Australia, was a man who “… had never travelled beyond the settled districts of Australia, who had no experience of exploration and who was notorious for getting lost on his way home from the pub.”7 This choice did not bode well for the expedition. Murgatroyd describes it as the reflection of a Melbourne society obsessed with class distinctions and manipulated by rich, powerful men.8

When screening candidates to accompany him on the expedition, Burke chose men with the “right connections,” paying no heed to exploration experience.9 Fortunately for the expedition and for all those interested in what became of it, one of the men Burke chose was William Wills, a young Englishman with a talent for surveying and science. Wills was hired on for the expedition as a surveyor, scientist, and third in command; he was intelligent, methodical, extremely competent, and completely dedicated to his work.10 Suffice it to say that an expedition originally called the Burke Expedition was later amended to the Burke and Wills Expedition based on the merits of the young surveyor.

The interior of Australia, although offering harsh terrain to explorers, did not present insurmountable barriers to those well-prepared for it. Stuart travelled light and fast,3 eventually crossed the continent completely from south to north and back, and is now recognized as Australia’s greatest explorer.32 Big John McKinlay, William Landsborough, Frederick Walker, and Alfred Howitt – other experienced bushmen with crews sent to rescue the Burke and Wills Expedition – travelled thousands of kilometres with “embarrassing ease” and never lost a man.11 The Burke and Wills Expedition lost eight – an Aboriginal guide and seven Europeans.12

In her book, Sarah Murgatroyd carefully and extensively documents all the things that went wrong with the Burke and Wills Expedition. I’ll simplify. As already stated, the expedition was poorly organized and poorly led, with none of the members having any previous exploration experience. Despite advice to the contrary, the committee ordered the expedition to start out at the onset of summer, rather than waiting for the cooler season.13 The expedition carried too much cargo with too little transport,14 exhausting men and beasts even before the most challenging desert portion of the journey began.15 Heavy rains repeatedly caused the party to bog down, slowing travel and contributing to the exhaustion of the men and transport animals.16 Burke alienated many of the men17 and made poor decisions en route, including dumping crucial supplies like lime juice (for prevention of scurvy) and medications.16 Hidden agendas appeared, with Burke splitting the party into two on the banks of the Darling River near Menindee,18 and again into two at Cooper’s Creek.19 The most damning decision Burke made was to continue pushing north past January 30 with Wills, King, and Gray when their food supplies were dangerously low.20

On February 11, the four men made it to Camp 119 near the mouth of the Flinders River, about 20 kilometres from the Gulf of Carpentaria.21 Then, overwhelmed by the almost suffocating humidity of the tropics and suffering from sleep deprivation, fatigue, and diseases caused by malnourishment, they turned back. Gray died en route.22 The other three reached Cooper’s Creek 127 days after leaving it, only to find the depot crew, which Burke had instructed to wait there for three months, had departed that very morning, April 21, 1860.23 Short on food rations themselves, they had left only a few supplies in a camel trunk buried near a coolibah tree into which William Brahe, the depot leader, had carved that enduring word ‘DIG’.23

Too exhausted and ill to catch up with the others, Burke, Wills, and King rested briefly and then, without leaving any message, set out for Mount Hopeless and Adelaide rather than following the same route south that they had earlier trod northward from Menindee. That was Burke’s second most damning decision, because Brahe, haunted by the thought that Burke might have made it back to Depot 65, returned to the Dig Tree before finally leaving Cooper’s Creek. He saw no sign of Burke, Wills, and King ever having been there and, of course, did not encounter them.24

Burke’s weakened and weary party soon realized their attempt to reach Mount Hopeless was indeed hopeless.24 Wills returned to Cooper’s Creek and deposited his expedition journals in the camel trunk under the Dig Tree. He never realized that Brahe had been there.25 Then, with his health rapidly deteriorating, he returned to Burke and King and sent the other two men to look for Aboriginal people to help them.26 Wills died alone of starvation, and Burke died on possibly the same day, with his revolver in his hand and King beside him.27 King found help from a band of Aboriginals28 who cared for him until he was rescued five months later by Howitt and Brahe on September 15, 1860.29

Such was the end of the Burke and Wills Expedition, its dead namesakes hailed as heroes by Melbourne and Victoria.30 Murgatroyd has a different take, stating, “Once Burke had been chosen as leader, the die was cast. The enterprise was doomed before the first camel was even saddled.”31

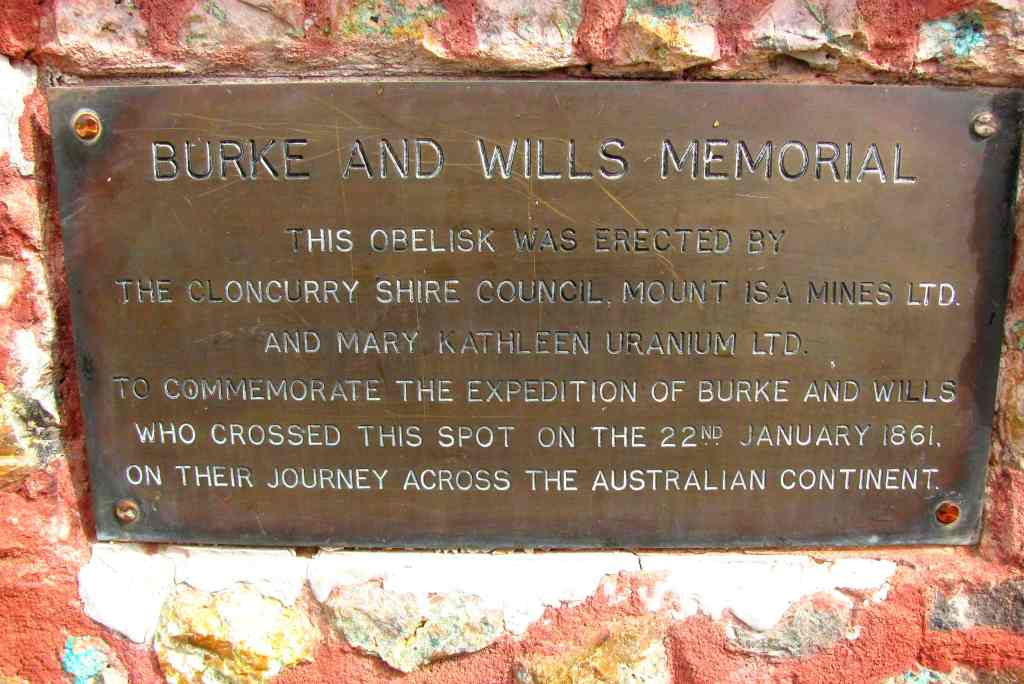

Burke and Wills Memorial (© Magi Nams)

References:

1. Susan Murgatroyd. The Dig Tree: The Story of Burke & Wills. 2002. Text Publishing, Melbourne, 372 p.

2. Ibid, p. 18; 3. Ibid, p. 44; 4. Ibid, p. 46; 5. Ibid, p. 1; 6. Ibid, pp.1-3, 339-40 ; 7. Ibid, p. 55; 8. Ibid, p. 66; 9. Ibid, p. 70; 10. Ibid, pp. 5, 81; 11. Ibid, pp. 337-338; 12. Ibid, p. 337; 13. Ibid, p. 82; 14. Ibid, p. 94; 15. Ibid, p. 118; 16. Ibid, p. 106; 213 ; 17 Ibid, p. 98; 18. Ibid, p. 122, 129; 19. Ibid, p. 164-166; 20. Ibid, p. 204; 21. Ibid, pp. 208-212; 22. Ibid, p. 228; 23. Ibid, p. 233; 24. Ibid, pp. 252-253; 25. Ibid, p. 258; 26. Ibid, p. 266; 27. Ibid, p. 274; 28. Ibid, p. 285; 29. Ibid, p. 289; 30. Ibid, pp. 336-337; 31. Ibid, p. 34

32. Wikipedia. John McDouall Stuart. Updated 15-Oct-2010. Accessed 19-Oct-2010. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_McDouall_Stuart