Young Rufous-bellied Pademelon in Baker’s Point Campground (© Vilis Nams)

The darkness of 6 a.m. arrived too early after a night during which Vilis and I awoke and pulled on track pants, socks, and sweaters for added warmth. The cold of Narawntapu National Park was so unexpected after our steamy nights in Townsville and mild east coast Tasmanian camping in Tasman and Freycinet National Parks.

While we ate our hot porridge breakfast at a picnic table, an adult rufous-bellied pademelon and her offspring foraged beside our campsite and hopped to within a few feet of us. Sunrise splashed pink onto lenticular clouds sculpted by winds high overhead, and at ground level, a cold wind caused us to wrap our sleeping bags around us while we ate.

An hour later, we returned to the plain adjacent to the Springlawn campground, which this morning was empty of the abundant herbivores of last evening. We did catch a glimpse of a common wombat racing across the grassy field, and of a male red-necked wallaby sunning himself near the edge of the woods next to the plain. Three flightless Tasmanian native hens foraged among ferns bordering the plain, the chicken-like birds’ heads continually moving as they pecked at the ground and strode among the ferns on sturdy legs. Silvereyes – small green and yellow songbirds with striking white eye-rings – and grey fantails flitted about in the shrubs. Eurasian coots and black swans swam on a freshwater lake adjoining the plain, forming graceful silhouettes against the early sunshine.

Field of Ferns and Grasses, Archer’s Knob Track (© Vilis Nams)

Leaving the plain, we hiked a sandy path northeast toward Archer’s Knob, passing through fields of ferns and tall shrubs. Silver banksias were particularly abundant, their canopies cluttered with yellow, bottle-brush blossoms and brown seed cones. The trail was cluttered, too, with tracks of macropods and creatures whose prints we didn’t recognize – far more than we’d seen on any other track we’d hiked in Australia. Where the trail passed through swamps, the vegetation was dominated by slim, grey-barked trees tufted with canopies of needle-like leaves that crowded tightly against each together and cast a gloomy, almost ghostly air. Thornbills tossed bright, lively calls into that gloom, and the scats of wombats adorned the boardwalk and trail crossings. Pademelons sheltering within the cover of protecting shrubs hopped away at our approach.

Tracks, Archer’s Knob Trail (© Vilis Nams)

Swamp, Archer’s Knob Track (© Vilis Nams)

From a bird hide perched on the edge of the lake, I spotted black swans, Australasian shelducks patterned with rust and black, a single musk duck with its peculiar flap of skin hanging from its beak, and hundreds of Australian wood ducks feeding on the shore where we’d walked earlier in the morning. Looking across to the far side of the lake, I observed wallabies resting and grooming their fur in the sun. Again, as during last evening, I received the impression that Narawntapu was blessed with an incredible richness of wildlife.

Carrying on toward Archer’s Knob, we encountered many more pademelons feeding or resting near the path and noted their trails, which reminded me of snowshoe hare trails in Canada. I began christening the trails – Pademelon Road, Pademelon Drive, Pademelon Crescent and so on, with my favouite being Pademelon Parade. While we hiked, little wattlebirds foraging for nectar in the silver banksias screeched and barked out their distinctive “kwock” calls, as though alerting the whole neighbourhood to our presence.

Here I am in the Moorland on Archer’s Knob Track (© Vilis Nams)

The Archer’s Knob Track led us through a surprising variety of habitats – scrub, open fern fields, swamps, and then stunted forest, where the trail became a series of switchbacks up the side of a steep slope until it emerged onto moorland dominated by grass-trees, heath plants, and sheltered banksias.

From the summit, we gazed out to the north over an azure Bass Strait, beyond which mainland Australia lay invisible in the distance. Breakers roared onto shore in frothing white ribbons that spilled onto a beach the colour of pale cinnamon.

Grass-tree Moor atop Archer’s Knob, with View Northeast to Badger Head (© Vilis Nams)

To the southwest, we looked out over the plains of Narawntapu and the narrow peninsula jutting toward Baker’s Point and our campsite. Resting atop the Knob, we munched apples and the last of chewy candy strips we’d bought at Salamanca Market, and then headed down off the Knob. We hiked quickly, knowing we again had hours of driving ahead of us before we would reach today’s destination of Cradle Mountain – Lake St. Clair National Park at the northern end of a vast chunk of protected World Heritage Area that extends from north-central Tasmania to the state’s south-western tip.

Vilis and Archer’s Knob Track, Nawrantapu National Park, Tasmania (© Magi Nams)

Vilis Shaking out Tent while Breaking Camp (© Magi Nams)

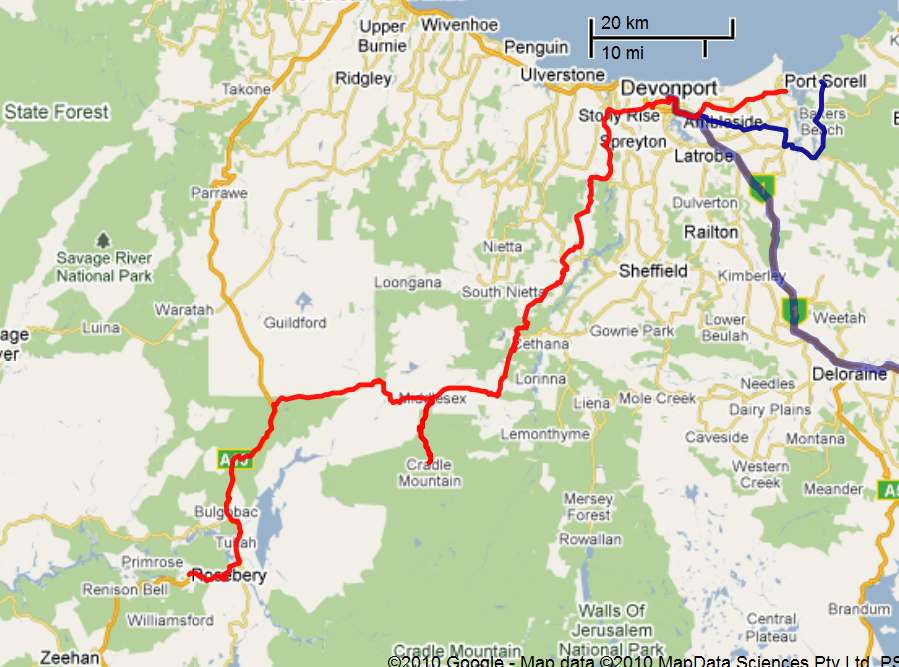

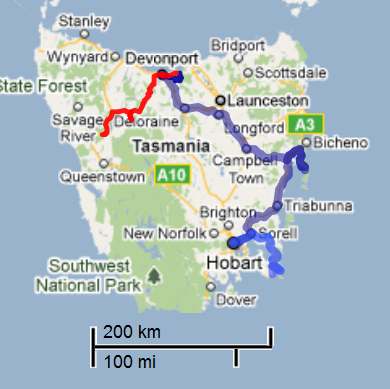

After breaking camp, we drove to Devonport through lush farmland lying dappled beneath a collage of blue sky and grey cloud. In the town, we purchased warm toques for both of us and gloves for me, knowing we’d need them in the mountains. At 3 p.m., later than we expected, we headed south alongside the broad, blue Mersey River, driving past apple orchards and rolling farms on steep ranges of hills that punched into the sky. Beyond Sheffield, which advertised itself as the ‘Town of Murals,’ the massive span of Mount Roland reared up to the south.

Mount Roland (© Magi Nams)

On entering the Mt. Roland Regional Reserve of open gum forest with a thick shrub understory, we discovered yet again that, although Tasmania is a small state, its distances are deceptive. As on Saturday and yesterday, our estimated driving time ballooned as we embarked on a series of twisting, climbing, and dropping curves that transformed into tight switchbacks rivalling those of the Black Spur and Kinglake roads near Melbourne. Rain set in, and the Alto struggled to scale the peaks, taking steep climbs in 3rd gear, 2nd gear, and occasionally, 1st gear.

Middlesex Plains ( © Magi Nams)

Beyond Moina, tree ferns appeared in the forest’s cluttered understory, and the highway led us onto Middlesex Plains, a rugged rangeland bearing old tree stumps as evidence of past logging. Cattle grazed beside the road, in several areas without fencing separating them from traffic.

The rain dogged us all the way to Cradle Mountain, where cloud and precipitation appeared to be solidly socked in. At the visitor centre, we learned that the forecast was for more rain for the next three days. That information, along with Cradle Mountain’s mega-tourism atmosphere and the fact that we could only gain access to the park via a shuttlebus, caused our planned two-day backpacking excursion in the park to suddenly lose its appeal.

Cradle Mountain Shuttlebuses (© Magi Nams)

Leaving Cradle Mountain, we linked up with C132 heading west through steady rain. Dense, wet forest with impenetrable walls of tall shrubs lined the road, the shrubs trimmed back from the highway’s verges into carved, concave borders that arched out above the pavement. At times, we felt as if we were driving through a green tunnel hung with clouds and washed by rain.

Tasmanian West Coast Rainforest (© Magi Nams)

On reaching the A10, the main north-south traffic artery through western Tasmania, we headed south into wild, heavily forested country. ‘Welcome to the West Coast,” a sign greeted us, and we realized that we had crossed Tasmania’s dividing range of mountains. In contrast to the Northern Midlands we had driven across en route to Narawntapu, which were open and dry in the rainshadow of the uplands, the West Coast forests rose lush and tall, nourished by rains sweeping in from the ocean and falling onto the coastal region after encountering the barrier of the mountains. “This feels like it could be the west coast of British Columbia,” I commented.

“Or New Zealand,” Vilis added.

With the rain bringing dusk on quickly, we abandoned the idea of camping and instead looked for a motel room in Tullah. Unfortunately, the only room on offer was a tacky econo room with a cracked window, so we drove on.

Next up was Rosebery, a mining town nestled at the base of cloud-shrouded hills, where our accommodation- and supper-seeking efforts became a comedy of errors. When searching for a lodge advertised on a sign post, we drove onto the zinc mine site instead, before discovering the lodge hidden by a wall of plants near the mine. It had no vacancies, so we made our way to Top Pub, the local hotel, where the manager gave us the wrong key and sent us to a room with an unmade bed and dishes on the mantle, clear signs that it was already occupied. We attempted to order supper in the hotel restaurant, but gave up after waiting 20 minutes without the waitress even visiting our table. Supper ended up being a small meat pie – the last one left – bought from a convenience store and supplemented with lunch fixings intended for tomorrow. All Vilis and I could do was laugh, thankful we’d found shelter and plenty of hot water for luxurious showers that washed away camp dirt and the chill of the rain.

Today’s fauna: *Tasmanian native hens, masked lapwings, *Eurasian coots, black swans, white-faced heron, grey fantails, silvereyes, Tasmanian thornbills, *musk duck, Australian wood ducks, *Australian shelducks, forest raven, superb fairy wren, little wattlebirds, silver gull, welcome swallows, rufous-bellied pademelons, common wombat, red-necked wallaby. (*lifelist sighting)