Light cloud blanketed the sky over Townsville as I walked within Bicentennial Park early this morning, listing all the birds I saw and heard. As I did so, it occurred to me that Australia’s birds are so much more visible than its mammals and other vertebrate life forms that I’ve presented posts heavily weighted in their favour. To somewhat remedy this partiality, I decided to devote several posts this week to iconic Australian mammals and reptiles. The first of these is the platypus.

The platypus, like the koala, saltwater crocodile, and kangaroo, is an animal I wanted to observe not only in a zoo or wildlife sanctuary, but in its natural habitat in the wild – that natural habitat being rivers and lakes in eastern Australia from tropical Cooktown in North Queensland to the alpine reaches of Tasmania.1 Vilis and I scanned the waters of Platypus Bay, Lake St. Clair in Tassie in March, and the green pools of Stoney Creek in Queensland’s Girringun National Park in May – both reputed to be good sites for spotting this shy aquatic mammal with its peculiar rubbery bill – but with no success. In early July, after driving our son Janis to Bundaberg to work as a veggie picker, Vilis and I made a detour to Eungella National Park (see July 6 post; http://maginams.ca/2010/07/06/) during our return trip to Townsville in order to check out Broken River, which my travel guide describes as the best site to observe platypuses in Australia.2 There, we had success.

We arrived at the viewing platform above a wide green pool in the Broken River late in the afternoon, just before dusk. Standing silently in the dim lighting of the rainforest-shrouded waterway, we eventually spotted a small, moving shape on the surface, its distinctive bill broad and dark, its back a rounded swell bulging upward from the water, and its flat tail floating behind it. Early the next morning, we returned with the hope of snapping photographs of platypuses, knowing they’re active at dawn, dusk, and sometimes in the night.3 Again, we had success, first observing at least two different platypuses that poked along near the shore and swam and dove within the river pool. One of the platypuses had appeared suddenly within the water, leaving a recess in the far bank that I thought might be a burrow entrance. As is the lot of many who seek platypuses, we were able to watch these only from a distance that rendered them interesting but relatively unclear shapes in the water.

Platypus, Broken River (© Vilis Nams)

Platypus, Broken River (© Vilis Nams)

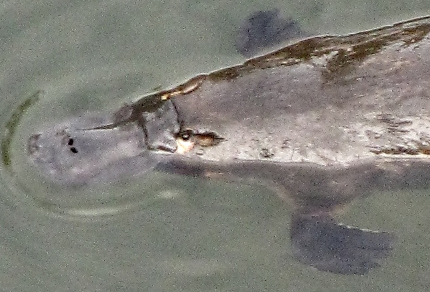

After leaving the viewing platform, we met an excited couple who informed us they’d watched a platypus in the river directly beneath the bridge. Following up on that tip, we crept close to the shoreline and spotted a platypus at much closer range, giving us good views of its webbed feet, dense fur, broad tail, and bill. Nostrils were clearly visible on the top of the grey bill, as were the grooves on the sides of the platypus’s head, in which small eyes were visible (and in which inconspicuoous ears are positioned behind the eyes3).

Platypus at Broken River, Eungella National Park, Queensland (© Vilis Nams)

Platypuses, with their rather astonishing collection of physical attributes – rubbery bill, webbed feet, poison-injecting spurs (males), no teeth, mammary glands but no nipples (females), single body opening for waste ejection, eggs rather than live-born young – turned the scientific world on its head when a dried skin was brought to England in ca. 1798.4 Before being accepted as derived from an existing animal, the specimen was proclaimed a fake that had been constructed by a prankster taxidermist who attached a duck’s bill to a body built of pieces of various mammals.4 Eventually, the platypus was also accepted as a true mammal and is now classified as a monotreme in an entirely different taxonomic group from the marsupials, of which Australia has many and the rest of the world has few, and the remaining mammals known as eutherians, of which Australia has few and the rest of the world has many. (See April 14 post on monotremes, marsupials, and eutherians; http://maginams.ca/2010/04/14/ )

Only three species of monotremes exist in the world today – the platypus and long-beaked and short-beaked echidnas, with the last species also occurring in Australia.5 In contrast to the short-beaked echidna, which is specialized as an ant-eater, the platypus dives within rivers or lakes to feed on bottom-dwelling invertebrates.5 Highly sensitive receptors in pits in the platypus’s bill aid it in locating prey and navigating underwater (it closes eyes and ears when diving).6 The platypus stores captured prey items in cheek pouches during a dive and grinds them up with hard plates at the rear of its jaws while it floats on the water surface.7 Vilis and I observed several dives and bouts of surface floating, when the platypuses were likely chewing their freshly acquired meals.

Like other aquatic mammals, such as the beaver or muskrat of North America, the platypus possesses a streamlined shape and thick, insulating fur.6 Its forefeet are fully webbed and provide the animal’s primary means of propulsion, while its hind feet are partially webbed and act as rudders while swimming or anchors while digging burrows in river banks.6

Platypuses are relatively small, with males larger than females. A typical male platypus is about 50 centimetres from the tip of its bill to its tail tip and weighs about 1700 grams, while a female is around 43 centimetres long and weighs only 900 grams.6 Males become aggressive during the spring breeding season, rushing other males and sometimes attacking them with their poison-injecting spurs.8

Spring is also when mating occurs and the female platypuses lay their eggs, which they incubate by holding them with their tails against their abdomens while curled in burrow nests.9 After about a week of incubation, nestling platypuses hatch from the eggs and begin to feed on their mothers’ milk, which is ejected from two milk patches or areolae onto the belly fur.10 Young platypuses spend much of their first summer within the burrow, nursing and growing.11 Towards the end of the summer, they leave the burrow and begin feeding on benthic (bottom) invertebrates,12 gradually assuming the lifestyle of the intriguing adults Vilis and I observed at Broken River.

Platypus, Broken River, Eungella National Park, Queensland (© Vilis Nams)

Today’s birds: channel-billed cuckoo, peaceful doves, brown honeyeaters, rainbow lorikeets, white-gaped honeyeater, olive-backed oriole, mynas, Australian white ibises, white-breasted woodswallows, brush cuckoo, blue-faced honeyeater, figbirds, Australian magpie, magpie geese, rock doves, house sparrows, white-throated honeyeater, little corellas, great bowerbirds, bush stone-curlew, magpie-larks, masked lapwings, rainbow bee-eaters, welcome swallows, helmeted friarbird, leaden flycatcher, little black cormorant, eastern koel, golden-headed cisticolas, pied imperial-pigeons, red-backed fairy-wrens, pheasant coucal, nutmeg mannikins, sulphur-crested cockatoo.

References:

1. Tom Grant. The Platypus: A Unique Mammal. 1995. University of New South Wales Press Ltd, Sydney, p. 15; F.N. Carrick. Platypus. In: Ronald Strahan, editor. The Mammals of Australia. 1995. Reed New Holland, Sydney, p. 36.

2. Emma Greg. The Rough Guide to East Coast Australia. 2008. Rough Guides, New York, p. 513.

3. Grant, p. 3; 4. Ibid, p. 5.

5. Ronald Strahan. Order Monotremata – Platypus and Echidnas. In: Ronald Strahan, editor. The Mammals of Australia. 1995. Reed New Holland, Sydney, p. 32-35.

6. Grant, p. 2.

7. Carrick, p. 37.

8. Grant, p. 42; 9. Ibid, p.39; 10. Ibid, p. 35; 11. Ibid, p.45; 12. Ibid, p. 53.