Two serendipitous observations led me to explore the story of Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer and the coelacanth, possibly the greatest scientific find of the twentieth century.

Recently, while Vilis and I were strolling on Rhodes University campus, I noticed a building with a name that sent a thrill through me: Courtenay-Latimer Hall. “I wonder if that building was named for Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer,” I commented. “She was the woman who realized that a big fish brought to the docks by a fisherman wasn’t any ordinary fish. It was a coelacanth. Maybe the scientist who confirmed its identity was based at Rhodes.”

“Or maybe she was a scientist working at Rhodes,” was Vilis’s reply.

I first heard the remarkable story of the coelacanth when I was a little girl in grade school in Alberta, Canada, half a world away from Grahamstown. A teacher told my class that in 1938, an amazing fish had been caught off the coast of Africa. It was unlike any fish known, except a group of fishes believed to have gone extinct millions of years ago – the coelacanths. And that’s what it proved to be – a coelacanth. The magic of that story, the unlikelihood of such a thing happening, completely captivated me. I didn’t know then about Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer’s role in the story.

Five years ago, while in Australia, I had stumbled across Courtenay-Latimer while reading Sean B. Carroll’s book, Into the Jungle: Epic Adventures in the Search for Evolution, which inspired me to start this blog. Based on what I had read, I recalled that Courtenay-Latimer had made a point of letting fishermen know she was interested in unusual fish they might catch, but I didn’t remember what her position was. And then here I was in Grahamstown, staring at a building with her name on it.

Two days after noticing Courtenay-Latimer Hall, Vilis and I walked through the rain to the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity (SAIAB) on a corner of Rhodes University campus to listen to a talk about the Okavango Wilderness Project in Angola. As we entered the building, I saw a large fish – a very distinctive fish with lobe-like fins and a thick tail – mounted in a pale greenish-blue medium that simulated water. Instantly, I knew what it was – a coelacanth. (Tap on photos to enlarge.)

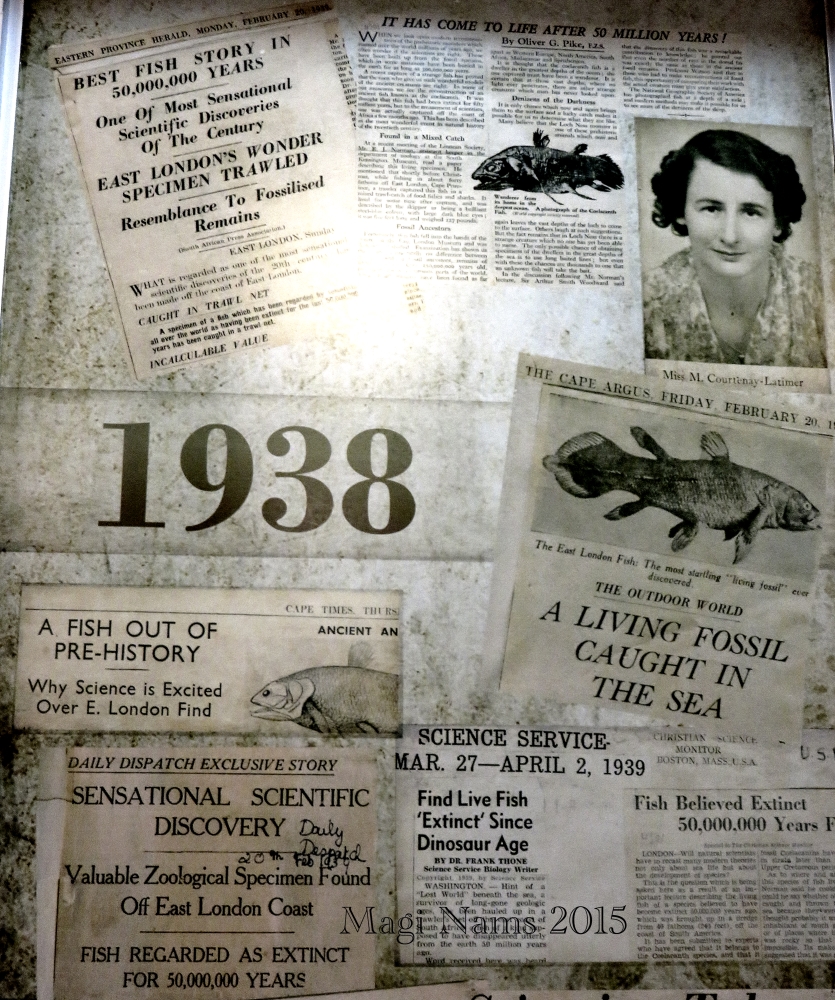

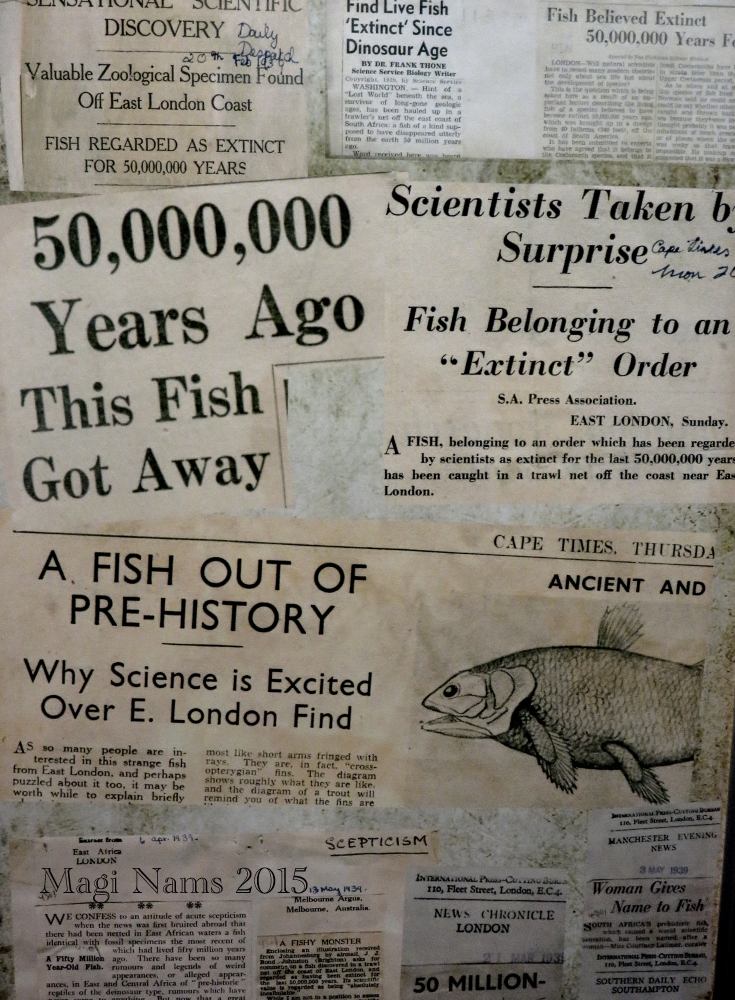

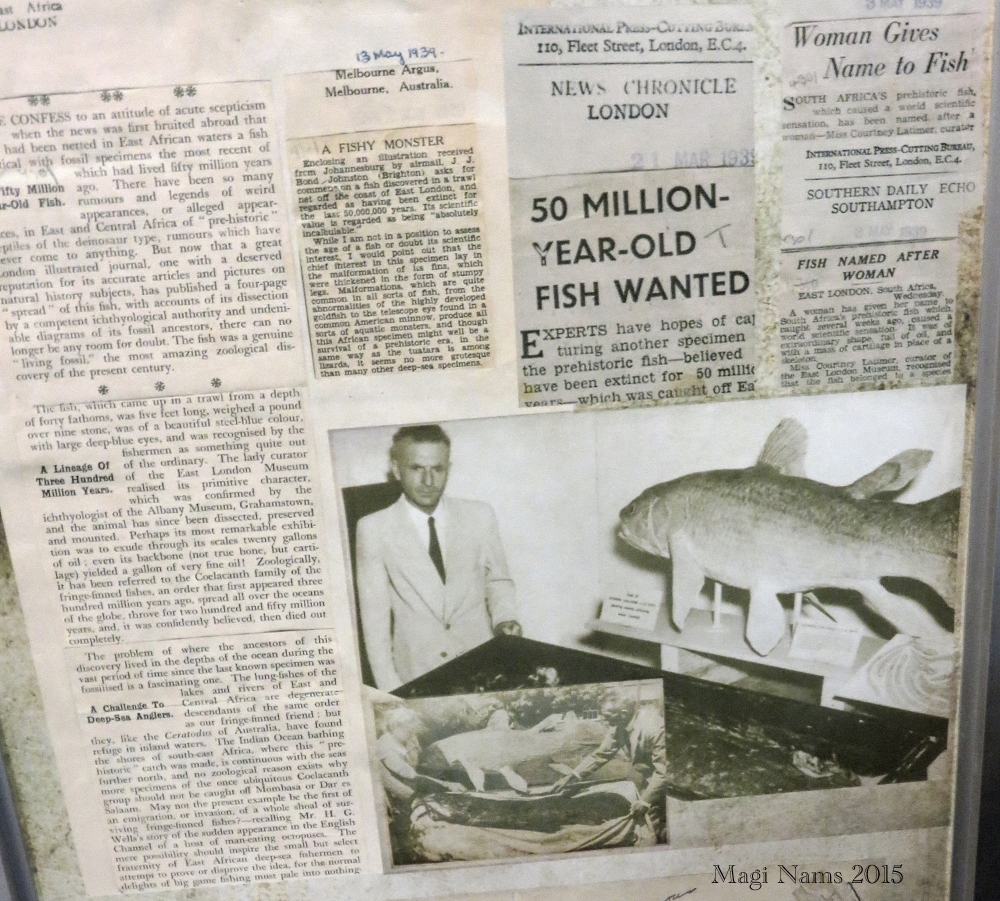

On the wall next to the fish was a collage of newspaper articles. And there she was – Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer, with her dark hair, serious eyes and gentle smile. A naturalist from a young age, she had been awarded the position of curator of the East London Museum (about 160 kilometres from Grahamstown) despite the fact that she had had no formal training in the natural sciences.

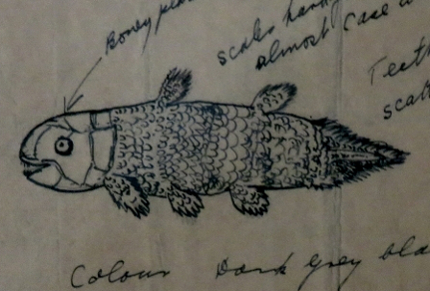

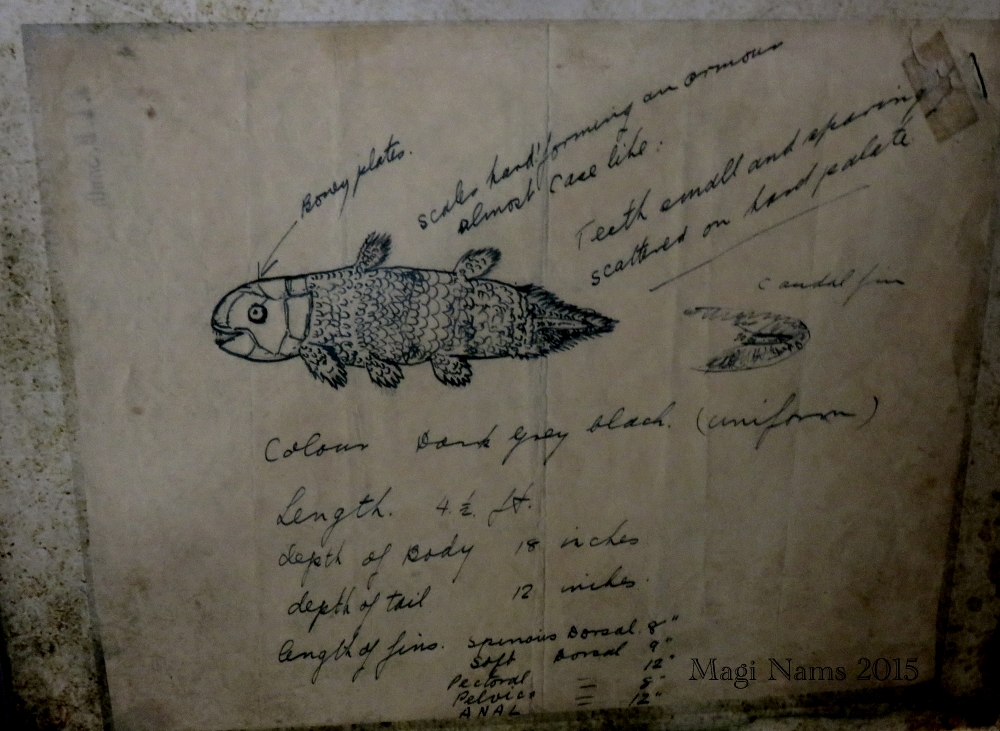

On December 22, 1938, while checking fishermen’s unusual catches on the East London dock, she had spotted a strangely beautiful fish. Nearly five feet long, it was a pale purple-blue in colour, with white specks, and bore an iridescent blue-green-silver sheen. The fish was covered in hard scales and had four lobed fins that resembled rudimentary limbs. It also had what Courtenay-Latimer later described as “a strange puppy-dog tail.” She had a taxi haul the fish to the museum, where she took measurements, drew a sketch of it and wrote a letter to J.L.B. Smith, a chemistry lecturer and amateur ichthyologist at Rhodes University. Then she desperately tried to find a means of preserving the fish. In the end, a taxidermist mounted the fish, sans internal organs. It’s still on display in the East London Museum.

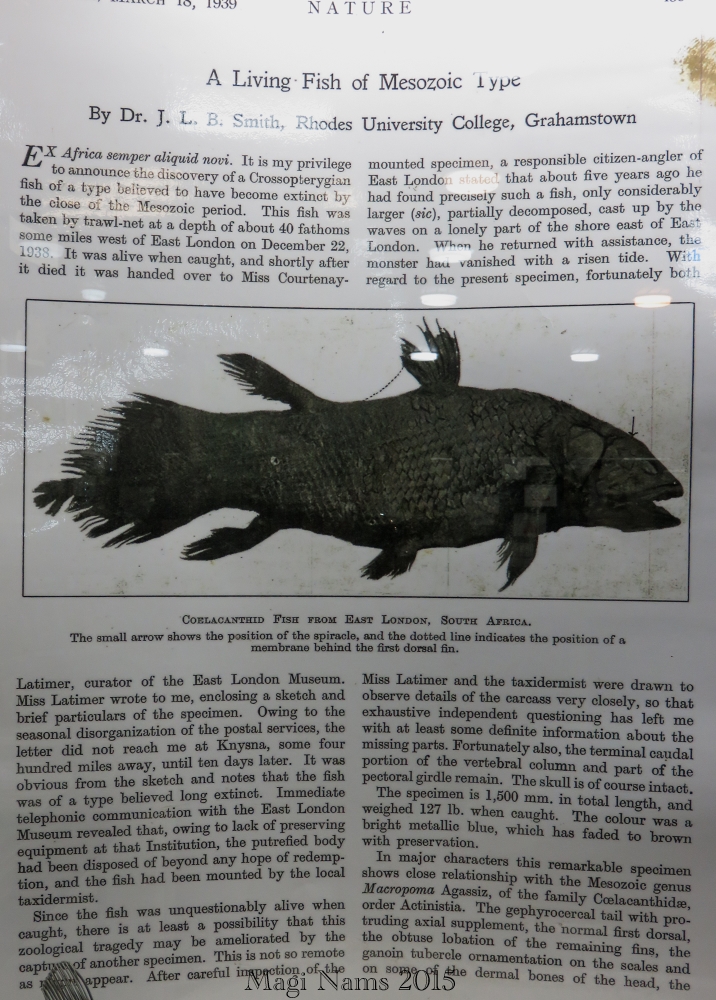

Ten days after Courtenay-Latimer had sent the letter describing her find, Smith had received it. He’d studied the drawing and felt as if “a bomb seemed to explode in my brain.” Immediately, he’d recognized that he was looking at a fish of the coelacanthid family that had been thought to be extinct for over 50 million years. Smith published the discovery in the preeminent scientific journal Nature on March 18, 1939, naming the fish Latimeria chalumnae, after Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer and the river near where the fish had been caught at forty fathoms in the West Indian Ocean.

Newspapers went wild. The discovery of the coelacanth was hailed as possibly the most important science discovery of the 20th century. Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer continued to work as curator of the East London Museum until 1973 and was awarded an honorary doctorate by Rhodes University. She died in 2004, at the age of ninety-seven.

Smith found the second extant coelacanth in 1952, caught by a fisherman offshore from the Comoro Islands north of Madagascar.

In 2000, the first coelacanths seen alive in their natural habitat were sighted in a deep canyon at Sodwana Bay on the north coast of South Africa. In 2001, the SAIAB (formerly named the JLB Smith Institute of Ichthyology) founded the African Coelacanth Ecosystem Programme to conduct coelacanth ecosystem research aimed at preserving the critically endangered coelacanths, thought to number in the hundreds.

A different species of coelacanth, Latimeria menadoensis, was discovered in Indonesian waters in 1997. And so, the legacy of Marjorie Courtenay-Latimer and the coelacanth lives on.