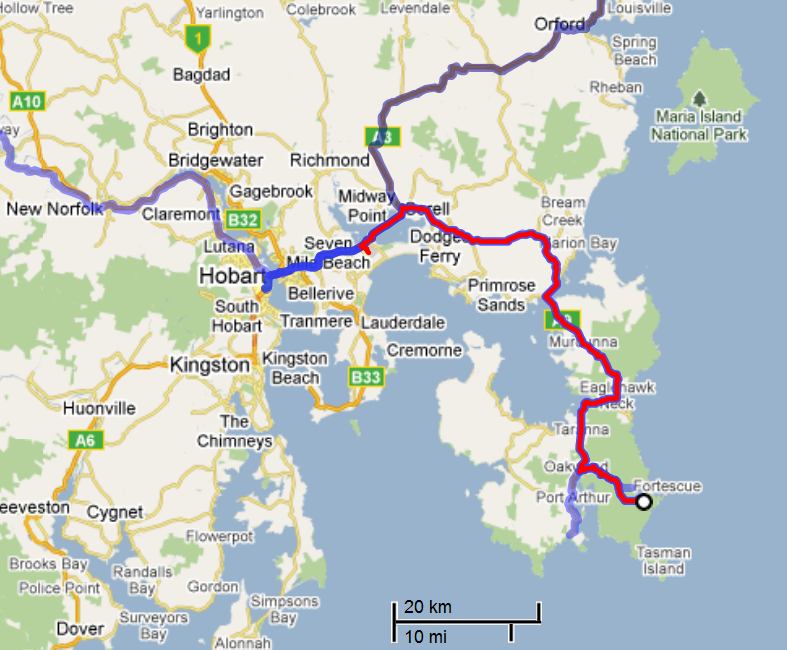

After days of dragging ourselves out of bed before dawn, we finally slept in, cozy in our sleeping bags. Once again, Fortescue Bay had granted us a mild night, and on rising we felt rested, rather than chilled. Vilis cooked up the last of the oatmeal for breakfast, after which we broke camp and re-packed our luggage for the flight to Townsville. In the midst of those preparations, Vilis checked the travel itinerary and discovered that our flight was scheduled to depart from Hobart two hours earlier than he had thought. Suddenly racing against time, we finished packing and hurried onto that squeaky beach to take a plunge into the cool, refreshing Tasman Sea.

Bidding Fortescue Bay farewell, we drove the dusty gravel road out to the A9 and, at Taranna, entered the Tasmanian Devil Conservation Park. With only 40 minutes to spare for the park’s wildlife inhabitants, we ignored everything but the devils. Fortunately, we caught the tail end of a feeding session and were able watch two devils fight over roadkill. A male and female, both seven years old and which had bred in the past but were now beyond mating, the two devils ripped at the meat and snarled viciously. On hearing the snarls, Vilis and I grinned at each other. Those were definitely the sounds we had heard at Lake St. Clair.

Young Tasmanian Devil (© Vilis Nams)

The devils were smaller than we had expected, but had big, blocky heads and massive jaws with large teeth. A park interpreter who had fed the devils told us those jaws and teeth could bite through 8 centimetres of bone. He went on to inform us that Tasmanian devils are primarily scavengers, feeding on carcasses up to two weeks dead and, thus, acting as part of nature’s clean-up crew. The old male and femae bore scars and open wounds on their heads, making it easy to see how Devil Facial Tumour Disease or DFTD (a transmissible cancer spread through biting that has devastated Tasmania’s wild devil populations1) has spread so quickly.

Adult Male Tasmanian Devil with Wounds on Flank (© Vilis Nams)

We learned a little of the reproductive biology of devils, too. The interpreter told us that the female devil produced four young per year for four years during her breeding career. She actually gave birth to twelve young the size of rice grains each year (at the same time), but eight of those young lost out in the race to the female’s four teats and died. The successful young finished their development within the female’s backward-facing pouch, and were out of the pouch at three or fourt months of age. Then, they either clung to their mother’s fur when she was out and about, or were left in a den. Young devils are apparently extremely good climbers, which they need to be, since adult male devils eat young ones if given the chance.

While the guide led other park visitors to view the wallabies and kangaroos, Vilis and I observed the old female devil in her den, which we were able to do by crawling through a tunnel to a plexiglas window looking into the den. She groomed her fur and sat back on her haunches in order to clean her pouch and genitals with her tongue. When she settled down to rest, we crawled out of the observation tunnel and spotted a devil standing atop a rock in a different pen. As we neared the pen, the devil scampered down from the rock, romped to near the enclosure wall, and gave away its young age by flopping onto the grass like a puppy.

Male Tasmanian Devil Dragging Female to Den (© Vilis Nams)

Nearby, two adult devils rested in a den. Soon one of them, which we identified as a male, rooted the other, a female, out of the nest of dried grasses and ferns, apparently intent on copulating. She ran to another den, but the male dragged her back to the first den and attempted to perform copulation on his unwilling partner. Apparently, there’s not much romance in the sex lives of Tasmanian devils.

Alas, our allotted time in the devil park had expired. I yearned to stay longer, but hurried to the Alto with Vilis, consoling myself with the fact that we’d both heard wild devils snarling in the night and had the opportunity to see them up close to observe some of their shenanigans.

The rest of the day was devoted to travel – the drive to the airport near Hobart, the flights to Melbourne and Townsville. The jets seemed such an extravagant convenience. Vilis and I flew from Hobart, at 43° South latitude, to Townsville, at 19° South latitude, in almost exactly four hours of flying time (both flights arrived early). We traveled a degree of latitude for every ten minutes of flight – an astounding feat of transportation. When we arrived in the sultry heat of Townsville’s dusk and saw palm trees everywhere, our destination looked and felt like a different country, another climate altogether from the cool freshness of Tasmania. That perception brought a couple things home to me: 1) Australia is a big country, spanning temperate, subtropical, and tropical climatic regions, and 2) Canadians living in Oz who are homesick for the feel of cold night air have only to hop on a plane to Tasmania, which is a whole lot closer than Canada.

Reference:

1. Adam Bostanci. A Devil of a Disease. 18 February 2005. Science, Volume 307, p. 1035.