Sphagnum Bog on Shadow Lake Circuit, Lake St. Clair National Park, Tasmania (© Vilis Nams)

Root ‘Steps’ on Shadow Lake Circuit (© Vilis Nams)

After the chill of the night, which reached a low of 5.7ºC in the Lake St. Clair campground, Vilis and I warmed ourselves with a hot porridge breakfast and set a brisk pace up through the black peppermint woodlands on the first leg of the Shadow Lake Circuit track, a 5-hour loop a dozen kilometres long. Tree roots crossing the path created natural steps, as did rocks, although none were the jumbled, broken plates we encountered on the Cape Hauy Track above Fortescue Bay during our first evening in Tasmania. We startled a mother rufous-bellied pademelon and her out-of-pouch young, and heard numerous birds unseen in the thick growth of shrubs alongside the trail or high in the canopies of trees. Above us, a thick layer of cloud crowded out brief sunny breaks.

The track led us uphill into damp, beech-dominated forest in which mosses and lichens blanketed virtually every surface – both horizontal and vertical – and wherein the surfaces of ground and logs were polka-dotted with the confetti of tan and yellow beech leaves. With an increase in elevation, the beech gave way to stunted upland forest with a low understory of heath shrubs.

Stunted Upland Forest on Shadow Lake Circuit (© Vilis Nams)

A rotting boardwalk carried us across a sphagnum bog, with mist a fine spray on our skin and hanging white among the trees. The squawks of little wattlebirds and chirps of grey fantails accompanied us as we climbed higher, encountering trees with an astonishing array of bark colours and patterns – some wearing skirts of peeling bark revealing pale green and orange skin, others mottled with olive, yellow, rust and grey, as in a paint-by-number picture, and still others with delicately-hued, flaking bark, like a gown adorned with lichen brooches.

‘Gown and Brooches’ Bark (© Vilis Nams)

‘Peeling Skirt’ Bark (© Vilis Nams)

‘Paint-by-number’ Bark (© Vilis Nams)

At the junction of the Shadow Lake and Mount Rufous tracks, we paused to munch apples and trail mix, tugging our toques down over our ears to warm them in the cold, damp air.

Vilis at Junction of Shadow Lake and Mt. Rufous Tracks (© Magi Nams)

Beyond the junction, the trail led us downward past eucalypts growing in a sphagnum moss bog, and then over a hilltop, onto a northeast-facing slope, and into a small grove of pandani – shaggy poles bearing topknots of green, pineapple-like leaves above a dress of dead, knife-like leaves which rattled when we brushed against them.

Eucalypts in Sphagnum Bog (© Vilis Nams)

Pandani Grove (© Vilis Nams)

From the pandani grove, the trail descended through a cold, damp beech forest gloomy with shadows and rich with mosses and lichens, as though it were some ancient kingdom fallen into ruin.

Beech Forest (© Vilis Nams)

Red-necked Wallaby (© Vilis Nams)

The trail continued to throw one vegetation type after another at us as we made our way downward toward Shadow Lake, evidence that particular species of trees and understory plants required specific environmental conditions that sometimes existed within only small areas, as with the grove of pandani, the only one we encountered on the track. After hiking through a copse of streaky-barked gums that looked as if they had been rolled in green and brown paints, we moved into open gum forest sharing the landscape with pockets of sphagnum bog and buttongrass fields or heath moor. We spotted a red-necked wallaby and scanned the buttongrass fields for ground parrots, but saw only a green rosella fussing in a gum at the edge of a moor. Late in the morning, the sun burned away much of the cloud cover, revealing a craggy peak and the shattered, boulder-strewn skyline of a jagged alpine ridge.

Heath Moor on Shadow Lake Circuit (© Vilis Nams)

Boardwalk over Fragile Moor on Shadow Lake Circuit (© Vilis Nams)

A long boardwalk carried us over fragile heath vegetation, and we noted mammal trails leading from the woods into the moor. Wombat and macropod scats littered the ground at the edge of the woods, causing Vilis to comment, “It could be a lively place in the evening.”

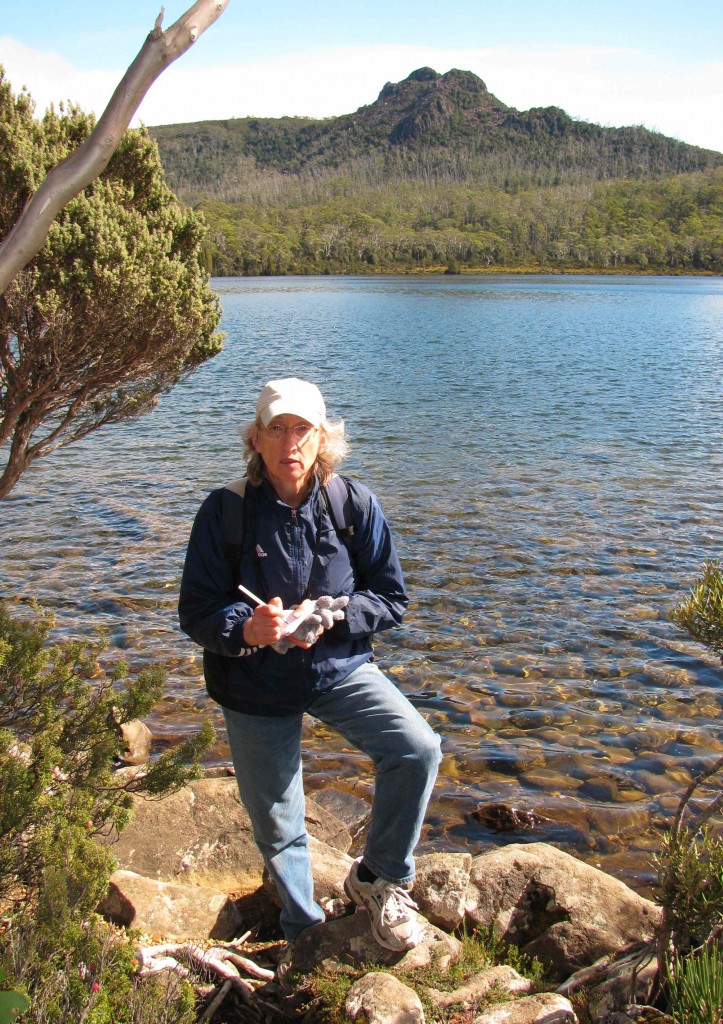

Soon after, we reached Shadow Lake, a small, clear mountain lake with water lapping at its shore, pushed by a fresh wind. “It’s the kind of wind that feels nice when you know you’ve got somewhere warm to go to,” Vilis commented.

Here I am at Shadow Lake (© Vilis Nams)

We hiked on, with Vilis almost immediately spotting a grey snake marked with black bands slithering away from the sunny ground at the trail edge and into shelter beneath a log. Likely, it had been basking prior to our arrival. “Tiger snake,” I told him. “There was a notice at the visitor’s centre saying that they’re on the move these days.”

“Is it poisonous?”

“Very.” Of Tasmania’s three species of snakes, the tiger snake and lowlands copperhead are both classed as dangerously venomous, while the white-lipped snake is only weakly venomous.

“So, we’ve seen our first really poisonous snake in Australia.”

“Second.” I reminded him of the red-bellied black snake that had raced away from me in Oak Valley near Townsville in late February.

At noon, with brilliant sunshine spilling down onto us, a fresh wind rustling the tree leaves, and the cheerful music of crickets in the air, the day felt so much like an autumn day in Nova Scotia.

Natural Rock Garden on Shadow Lake Circuit (© Vilis Nams)

During the last long leg of the circuit track, we hiked past a natural rock garden landscaped with buttongrass, cushion plants, and elegant, vertical heath shrubs, and then into open gum and heath woodland on rocky ground. Small ponds and trickles of water were caught among the boulders, and frogs sang a gentle chorus in the early afternoon warmth. Closer to Watersmeet, we hiked through dense stands of pink mountainberry and woolly tea tree. These species were conveniently identified for us by small interpretive plaques on posts, this section of track being a short portion of the Larmairremener cultural track.

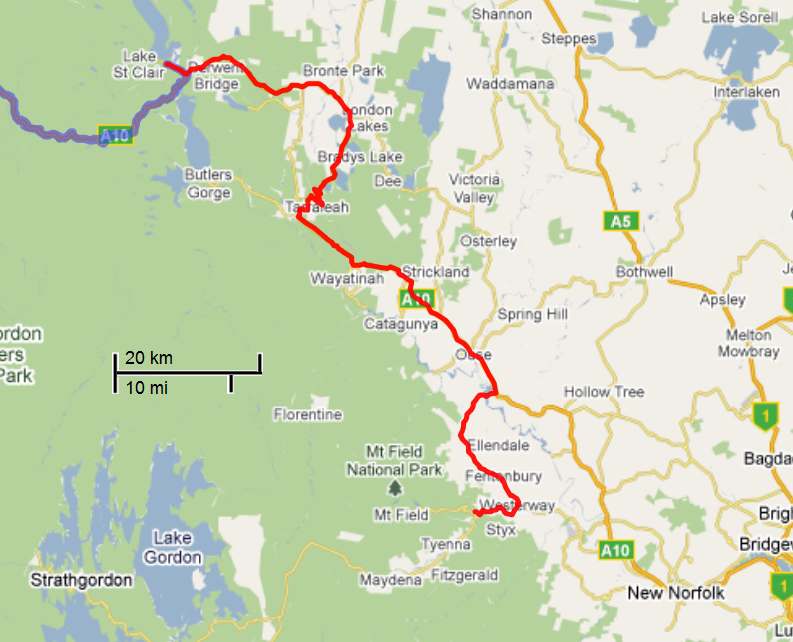

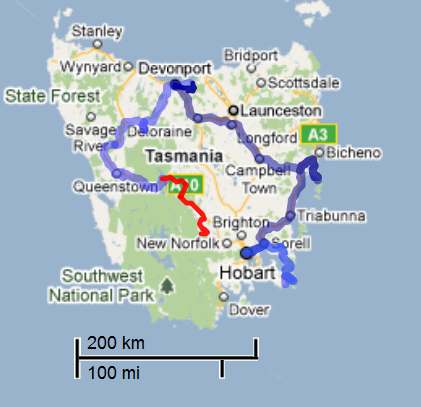

Five hours after setting out, we returned to the Lake St. Clair campground, replenished our energy reserves with buns and salami, and then drove southeast on the A10’s River Run Touring Route toward Hamilton and our next destination – Mount Field National Park. The highway, now east of the huge, north-south block of protected land in central and southwestern Tasmania, led us through open gum woods and buttongrass plains, and then into rough pastures backed by forested hills. We seemed to be driving across a plateau, not having descended much since Lake St. Clair, and passed numerous upland lakes scoured out by past glaciers. At last, we descended through gum forest and drove up and down mountainsides on yet another prime stretch of Tasmania’s twisting, mountain roads – this one leading into Tarraleah. The road traffic, we noticed, had been much lighter in the western half of the state than in the east.

South of Tarraleah, the landscape became a collage of clear-felled forest and eucalypt and pine plantations, giving notice that we were entering the state’s most hotly contested region of forestry versus environmentalists. It was isolated, with nothing but managed forests, the highway, a string of massive power towers, and the odd parcel of backcountry rangeland. Then, abruptly, the road emerged onto vast, far-reaching rangeland that had obviously been clear-cut in the past. The transmission towers rose high above cattle and sheep stations, the sheep’s wool blending in with dirty yellow grazing land. Tens of kilometres of bleached, rolling hills stretched before us, broken by the odd forestry plantation, patch of regenerating shrubs, vividly green, irrigated field, or small, country town.

North of Hamilton, logging trucks carrying thick logs – 3 or 4 to a truck – passed us on the highway. Hamilton itself was a dry hillside town featuring a surprising number of stone buildings. To the south and west of it, we drove by more logging trucks loaded with enormous sections of trees, and passed fields of hops tethered to overhead wires at Bushy Park and Glenora. The entire valley floor adjacent to those neighbouring small townships appeared to be covered with hop fields – some of which had been harvested.

Vilis (not feeding) a Young Rufous-bellied Pademelon (© Magi Nams)

A dozen more kilometres to the west, we reached Mount Field National Park, located just north of the Styx Valley and its forests of gigantic swamp gums – the world’s tallest hardwood trees, and thus, the world’s biggest flowering plants. We set up camp beneath the canopies of some junior members of that elite club. A young pademelon visited our campsite, and the laughing voices of 90 teenaged girls also camped at Mount Field permeated the air. I quickly discovered lineups of these girls waiting for showers, to use the loos and sinks, to apply makeup in front of mirrors, and to plug their laptops into the electrical outlets in the laundry room.

Before darkness fell, Vilis and I strolled through a grazed plain much like that at Narawntapu, although smaller, and observed Tasmanian native hens grazing near its periphery, as we had at Narawntapu. Then we sat on a bench beside the plain, waiting for darkness to fall before we hiked the 10-minute trail to Russell Falls and its glow-worm grotto. Exhausted due to last night’s cold and poor sleep, Vilis dozed against me while I looked out over the plain, spotting a couple of yellow-tailed black-cockatoos winging over the clearing.

Eventually, we roused ourselves and, as we began the walk to the falls, felt as though we’d stepped into another world. In the twilight, tree ferns flared their feathery fronds over the path. A liquid song lilted from the creek beside us. On both sides of the creek, the trunks of giant trees rose like shadowed columns in the dim light, as though guardians of a magical kingdom. Russell Falls spilled ethereal beauty over a dark rock ledge, like a veil of silver tears.

Again, we rested on a bench, dozing against each other while waiting for glow-worm blackness. In that brief, exquisite peace, I opened my eyes and saw the dim shape of a Tasmanian tiger standing silently a few feet away. I knew it wasn’t a living thylacine, although Vilis said that, after driving through the West Coast wilderness, he was no longer so sure that Tasmanian tigers are extinct. Rather, it seemed a ghostly presence, part of that enchanted twilight world of graceful ferns, giant trees, and water that whispered of times gone past.

We did see the glow-worms, which shone like tiny, blue stars against the wet darkness of the rocky grotto swept with moisture from the falls. Then we strolled back alongside the sweetly-lilting creek. A half moon spilled silver light onto the tree ferns and created shadows on the open plain, where pademelons grazed like herds of miniature, thick-haunched deer, and clusters of giggling teenaged girls with flashlights explored the night.

Today’s fauna: black currawong, little wattlebirds, grey fantails, green rosellas, Tasmanian native hens, scarlet robin, yellow-tailed black-cockatoos, rufous-bellied pademelons, red-necked wallaby, *tiger snake, land leech, glow-worms. (*lifelist sighting)