Eroded Mining Land at Queenstown (© Magi Nams)

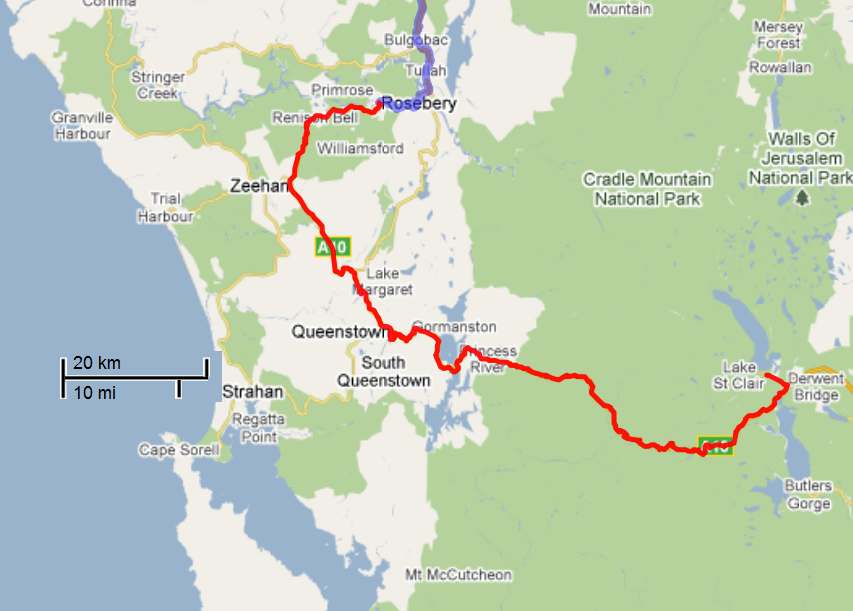

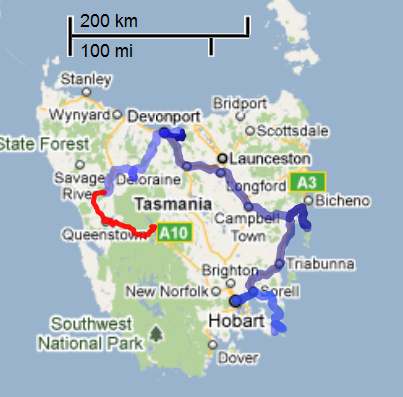

In rain and the dim light after dawn, Vilis and I departed from Rosebery after availing ourselves of a free breakfast of cold cereal and hot toast courtesy of the Top Pub. Heading south toward Queenstown, we drove first through lush rainforest in a valley between ridges of rain-shrouded hills. Then, with a shocking jolt to the senses and psyche, we entered the stark, barren realm of Queenstown, with its mined hills completely denuded of vegetation and eroded down to orange rock and gravel by the West Coast’s heavy rains. The copper-mining town itself was no more than a collection of ramshackle, metal-roofed houses with little effort put into their yards, and of false-fronted stores that looked as though they belonged to another era. So twisting was the highway through that utterly exploited and devastated landscape that the road signs were labelled with times rather than distances. We crept around bare rock curves surrounded by rubble vegetated by only a few colonizing grasses and shrubs. Clouds smeared our view, muting the devastation, and I wondered what kind of machines could do this to the earth.

East of Queenstown, we drove among hills that showed the fuzzy green beginnings of vegetation recovery. However, it was difficult to envision that ravaged landscape ever again supporting the lush forests through which we had driven yesterday and early this morning. Beyond Lake Burbury, forests reappeared as we entered Franklin – Gordon Wild Rivers National Park.

Nelson River (© Vilis Nams)

Pausing at Nelson Falls, we followed a rushing river upstream to the base of the falls, hiking through regenerating rainforest thick with ferns and tree ferns, grasses and slim-boled trees. The 35-metre cascade spilled out over terraces of rounded rocks, creating a white bell that blasted us with fine spray whipped toward us on a wind generated by the falling water.

Regenerating Rainforest on Nelson Falls Track (© Vilis Nams)

An interpretive sign at the Nelson Falls Track informed us that the area had been glaciated several times and had been logged and mined in the early 20th century. We also learned that the twisting, climbing and plunging Lyell Highway we’d been driving was originally cut by hand with pick and shovel.

Continuing eastward, we climbed over Victoria Pass, a broad notch in the mountains with a top elevation of 530 metres and a vegetative cover of regenerating forest.

Near Victoria Pass (© Magi Nams)

Heading east from the pass, the Lyell Highway led us on yet another tortuous path through the mountains and into drier landscapes. Again we took a break to hike one of Tasmania’s Great Short Walks, this one leading us to Donaghy’s Hill Wilderness Lookout.

Donaghy’s Hill Wilderness Lookout Track (© Vilis Nams)

Dense, small-leaved shrubs crowded the dry, hillside trail to Donaghy’s Hill, providing habitat for New Holland honeyeaters and other small birds. Interpretive signs introduced us to myrtle, a Southern Hemisphere beech species that dominates the forests of Franklin – Gordon Wild Rivers National Park. Other plant species identified along the trail included celery-top pine, giant gum-topped stringybark that can grow to 90 metres in height, pink mountainberry shrubs with white flowers and pink berries, and buttongrass. The buttongrass formed dense tussocks on the hillside and bore dry, brown, button-like flowers on long stems that curved out in all directions from the tussocks. The flower stalks resembled a wild collection of knobby toys on springs. The leaves were streaked with the colours of orange and rust and clay, their greens muted by autumn.

The track led us onto a spine of land that rollercoasted upward to the summit of Donaghy’s Hill, a fairytale hillock on which I could easily envision a quaint house belonging to a witch or elves.

Donaghy’s Hill (© Vilis Nams)

From the lookout’s wood platform secured to the summit rock outcrop, Vilis and I were greeted with spectacular views of forest-clad mountains and the wild, rushing Franklin River at the base of plunging slopes. Trails of cloud drifted upward from the river and hung over the peaks, and to the north, a rainbow was caught high in a mountain bowl. Patches of sunlight breaking through cloud and mist gilded the green slopes with strips of gold while the remainder of the forest brooded beneath dark rainclouds.

Having a 360º view, we saw thrusting, conical mountains in all directions and a gold-tinged wetland in a valley. Sweeping curtains of rain spread white veils over southern peaks. A trio of yellow-tailed black-cockatoos flew with long wing strokes over the ridge, their gorgeous lemon-yellow tail windows and cheek patches brilliant against their black plumages. Thrilled with the lookout, we felt as though we should have had to hike for 2 or 3 hours – not merely 20 minutes – to reach such a vantage point as Donaghy’s Hill.

View from Donaghy’s Hill Wilderness Lookout (© Vilis Nams)

Reluctantly, we descended from the lookout, wishing we could camp there and awaken to the sights and sounds of the mountains. After lunch at the car, we again continued eastward, our driving goal for the day the Lake St. Clair campground at the southern end of Cradle Mountain – Lake St. Clair National Park. The Lyell Highway led us over a mountain saddle and into a collage of buttongrass plains and gum forests growing in the rainshadow of the mountains.

Buttongrass Moor with Scattered Eucalypts (© Magi Nams)

Larmairremener Cultural Walk, with Banksias beside me (© Vilis Nams)

At Derwent Bridge, we turned north off the Lyell Highway and drove the short distance to the Lake St. Clair campground. In the visitor’s centre, we learned that the previous night’s low was a chilly 7ºC.

After setting up camp, we spent the remainder of the afternoon hiking the Larmairremener tabelti or cultural walk through the traditional land of the Larmairremener Aboriginal people, a band of the Big River Nation. Interpretive signs along the trail gave us a history of the Aboriginal people, who before the Europeans invaded and took their land, were part of a network of bands that traveled and traded throughout southeastern Tasmania. After the Europeans moved onto Larmairremener land, the 400-500 people fought for their homeland. Nearly all died, and in 1832, the 26 survivors – 1 child, 9 women, and 16 men – who had been promised “peace and prosperity” were sent from their homeland to Flinders Island, off Tasmania’s northeast coast.

Pink Mountainberry (© Vilis Nams)

While we walked along the trail, which led us through open black peppermint forest with an understory of pink mountainberry and banksias, I spotted a a black-faced honeyeater and female pink robin flitting about in shrubs alongside the trail, and a mixed flock of Tasmanian thornbills and silvereyes scolding us from within a tall banksia shrub. Fluttering leaves danced and rustled a wild wind song above us, and a boardwalk carried us over wet, swampy areas couched in the gloom created by dense, encroaching shrubs. Then we hiked through dry uplands where fallen beech leaves clustered at the bases of trees like spruce scales in a red squirrel midden in Canada. Another interpretive sign informed us that the Larmairremener people carried out planned burnings of the area to maintain paths and to encourage new growth of buttongrass, which attracted wallabies, kangaroos, and wombats, all of which were favoured food animals.

Descending into a creek valley, we passed moss- and lichen-covered beeches and celery-top pines that loomed over us like furry green-and-brown denizens of some enchanted forest. At Watersmeet, the junction of the Cuvier and Hugel Rivers, the streams joined for an energetic romp over boulders, creating noisy riffles and amber fountains of frothing, tannin-stained waters. On our return along the broad path through black peppermint forest to the campground, a half dozen male flame robins seared the grey deadfall on the forest floor with their brilliant orange-red throats and bellies, as if they really were small fires burning. Green rosellas – those slim Tasmanian parrots with yellow bellies and blue patches of feathers on their faces and wings – flushed one after another from trailside shrubs until we counted 10 in all.

Viis at Lake St. Clair Campground (© Magi Nams)

At our campsite, we quickly ate a hot soup supper and then hiked back into the forest, this time striding past Watersmeet to a hide overlooking Platypus Bay near the south end of Lake St. Clair. There we waited, silent and still, peering through peep-holes in the hide and hoping to spot a platypus swimming or grooming on the surface of the bay. The wind was still up, chilling us and whisking the surface of the water into small wavelets. An interpretive sign on our side of the hide mentioned that rough waters deter platypuses from swimming, so perhaps that was the reason we saw none in the 75 minutes we waited, scanning the near-shore water.

At last, with daylight slowly fading into darkness, we left the blind and hiked the remainder of the Platypus Bay circuit, which led us down to the shore of the lake, and then back up into the forest to join the main trail. As we walked that broad, pale avenue connecting the campground with the forest tracks, our eyes adjusted to the decreasing light levels, enabling us to walk comfortably through the darkness. When we approached the campground, the light of lanterns and campfires spilled white and orange into the night, and campers’ voices rang out. Then we heard a sound that stopped us in our tracks – two snarling barks in the darkness somewhere behind us, perhaps along the shore of the lake. Without saying a word, we turned and quickly retraced our steps, heading back into the darkness, hoping to hear more of those vicious-sounding barks, which could only have been uttered by a Tasmanian devil. (No dingoes in Tasmania.)

Only silence accompanied our steps, and having no idea where exactly the sounds had originated, we eventually turned back to camp. There, we bundled up in a full set of clothes plus toques and huddled down into our sleeping bags to combat the mountain cold. We awoke in the night, though, yanked from sleep into awareness by night-piercing snarls penetrating the darkness – the sound of Tasmanian devils defending their food. In Tasman, Freycinet, and Narawntapu National Parks, we had driven roads in the dark, searching for devils, yet at Lake St. Clair, they’d come to us.

Today’s birds: New Holland honeyeaters, yellow-tailed black-cockatoos, *Bassian thrush, Tasmanian thornbills, black currawong, *black-headed honeyeater, *pink robin, silvereyes, *flame robins, green rosellas (*lifelist sighting). Also heard barks and snarls of Tasmanian devils.