Lake Dobson Road (© Magi Nams)

Dawn at the campground in Mount Field National Park presented a cacophony of sounds – the mad laughter of kookaburras, the “kussicks” of green rosellas and squawking harangues of sulphur-crested cockatoos, the sweeter calls of songbirds, the boisterous barks of a dog in a neighbouring yard, and the grinding roars of logging trucks climbing steep inclines in the distance. Originally, we had intended simply to camp overnight at Mount Field and leave for the Styx Valley after breakfast; however, we were inspired by our walk to Russell Falls last evening and curious to see what else the park, which was established as a tourist reserve in 1885 and then set aside as Tasmania’s first national park in 1916,1 had to offer. Thus, we broke camp after breakfast and drove the 12-kilometre Lake Dobson Road through the park, making numerous stops to explore the towering forests and, at higher elevations, subalpine vegetation.

Near the base of the mountain, we strolled the Tall Trees Walk through deeply shaded wet sclerophyll forest dominated by the world’s tallest species of hardwood tree and flowering plant, Eucalyptus regnans, the swamp gum. An interpretive display informed us that regnans means ‘reigner’ or ‘ruler,’ which certainly seemed appropriate given not only the height, but also the girth of the trees. On leaving the Alto, I had seen a small bird flying high overhead and assumed it was far above the treetops; yet it flew directly into the canopy of a swamp gum and landed, giving me a rather startled perspective on the tree’s height.

Vilis and Swamp Gum on Tall Tree Walk (© Magi Nams)

The giant trees had thick, fibrous, moss-covered bark on their lower trunks; however, about a third of the way up the trunk, that bark peeled away and hung in tatters. Above that, long strips of pale grey and yellow bark decorated the surface of the trunk, making me think of a hand-painted silk scarf. In the treetops, sulphur-crested cockatoos tore the air with loud, wild screams, while yellow wattlebirds with small pendants of yellow flesh dangling from their cheeks hacked and coughed as though puking. “It sounds like we should have bits of vomit landing on us,” Vilis remarked. Together, the two species created an incredible racket as we walked the short trail.

The forest around us consisted of well-spaced mature swamp gums keeping company with an abundance of thin, very tall young gums, and an understory of tree ferns and little else. An interpretive sign informed us that few species of plants can survive beneath the swamp gum canopy, and that most of the young trees would die within a couple of years, with only 1 in 100 living to maturity. The tallest of the swamp gums in that forest patch was 79 metres.

Farther up Lake Dobson Road, we stopped at a viewpoint overlooking the wet gum forest on the lower slopes and faraway dry forest on hills beyond an expanse of rangeland. An interpretive sign informed us that “Mount Field National Park is a conservation island in a sea of farming and forestry – grazing lands lie to the east and the production forests of the Florentine Valley hug the park’s western borders.” We also learned that four major vegetation zones are present on the mountain – wet eucalyptus forest, mixed forest, subalpine woodland, and alpine mosaic. At Mount Field, the diversity of plant species increases with elevation, an unusual occurrence.

View from Lake Dobson Road (© Vilis Nams)

As we continued up the mountain, an interpretive sign introduced us to an implicate (tangled) mixed forest in which yellow gum, stringybark gum, and celery-top pine replaced the swamp gum as top trees, and in which a multi-trunked shrub called horizontal scrub created an incredibly tangled mess in the understory that would be, as the sign put it, a “bushwalker’s nightmare.” From that viewpoint, the road led us up a mountainside above a narrow gorge, with trees becoming progressively shorter, and more shrubs and heaths appearing as we drove higher. We crossed an open upland vegetated with a mix of trees and heaths, and dropped in elevation to Lake Dobson, beyond which the road continued as a steep track leading up to a skifield.

Subalpine Woodland at Lake Dobson (© Vilis Nams)

At Lake Dobson, we strolled briefly through subalpine woodland dominated by Tasmanian snow gum, a stunted, twisted-trunk species of eucalypt with bark streaked in shades of grey. Decidious beeches with yellow-orange leaves, and mountain pepper shrubs decked out in a profusion of red berries grew in the open forest understory, as did pandani. Boulders of dolerite encrusted with white, black, and orange lichens formed huge fields resembling avalanches chutes. An interpretive sign informed us that the boulders were “flowing” downhill, their gradual movement the result of the heaving action of freezing and thawing, as well as the movement of water running beneath them.

Mountain Pepper (© Vilis Nams)

‘Flowing’ Boulders (© Magi Nams)

Returning along the road, we pulled off next to Wombat Moor, an alpine mosaic vegetation zone on the higher ground we had passed en route to Lake Dobson. A wet, eroded path and sections of boardwalk led us uphill through a wet moor speared by occasional copses of snow gums. Mounds of alpine coral ferns with miniature, rectangular fronds, and clumps of pineapple grass having thrusting, silvery, blade-like leaves, dominated the moor vegetation. I had seen both plants in the moors while hiking the Shadow Lake Circuit yesterday, but hadn’t known their identities; here, an interpretive sign identified them for me.

Leaving the moor, we retraced more of the gravel road with its red snow stakes. An interpretive sign had informed us that it was constructed as a make-work project during the Depression years, employing 50 men for 3 years. They moved ahead at a pace of only 25 metres per day.

At the Seager’s Lookout trailhead, we parked the Alto and hiked upward through subalpine woodland and boulder fields to the lookout, a jumble of massive, smoothed rocks jutting out from a hillside. We scrambled around, among, and on top of the boulders, noting the piles of small rocks that had been placed atop isolated boulders by succesful rock scramblers. We discovered clumps of pandani growing among the twisted snow gums by the boulder outcrop, and looked out over a sweeping view of Lake Fenton to the west, and of the River Derwent valley to the east.

Vilis on Seager’s Lookout Track (© Magi Nams)

View of Lake Fenton from Seager’s Lookout (© Vilis Nams)

On our return to the base of Mount Field, we lunched in the campground, after which we again walked the short, tree-fern-shaded track to Russell Falls. I spotted a male pink robin perched on a lush blanket of moss covering a fallen tree, and other fallen giants lay in the valley and offered substrate for decomposers to do their work. The fibrous, brown trunks of tree ferns supported growths of delicate filmy ferns that resembled layered, green skirts, as well as sprouting bushy, forked spears of kangaroo fern. The air along the stream was cool and sweet, contributing to the track’s air of enchantment. Vilis and I found ourselves walking slower, more gently. At the end of the track, Russell Falls spilled over stacked layers and terraces of black rock having crevices that provided nooks for ferns and mosses to grow. In daylight, the glow-worm grotto was a wet, dark secret of slick, jumbled rock and tree fern trunks kissed by the spray from the falls. As we walked out from the falls, with swamp gums towering above us, I thought that there is a certain feeling that comes from walking in a place with tall trees – a feeling of humility, yearning, and inspiration all rolled into one.

Russell Falls (© Vilis Nams)

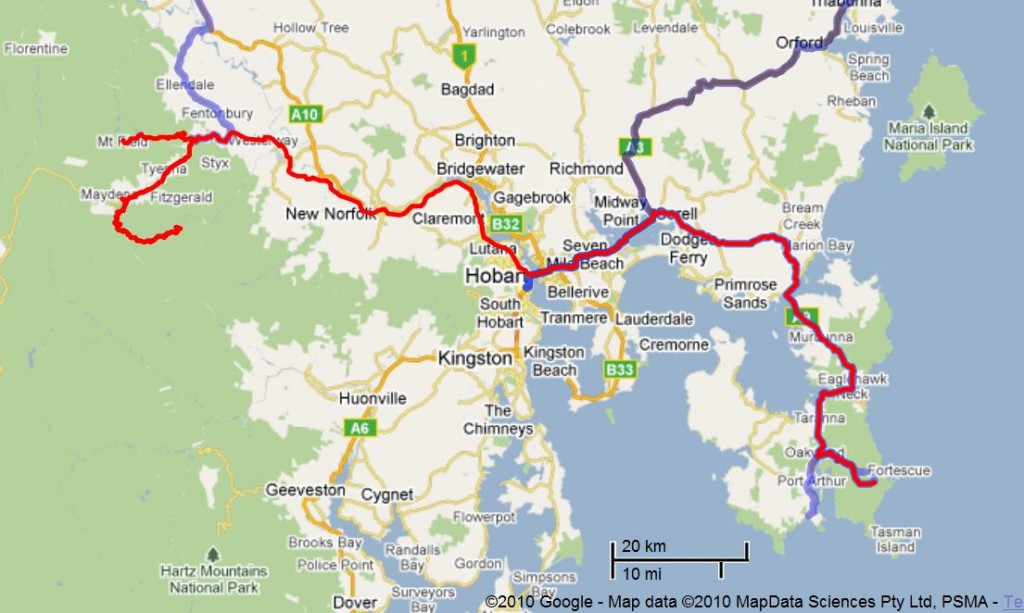

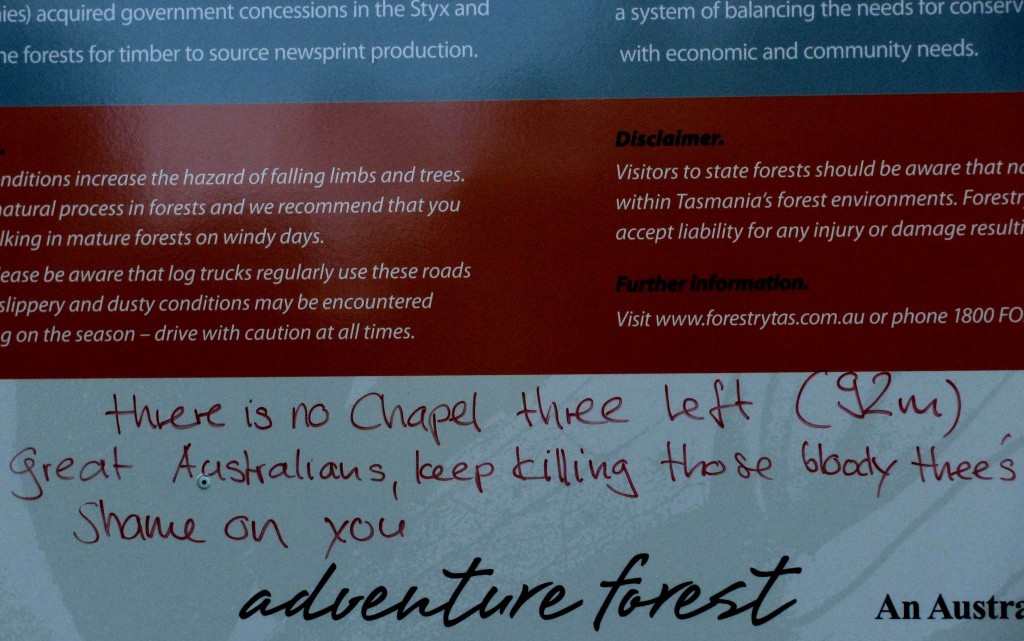

We left the surprising beauty and diversity of Mount Field National Park in early afternoon and headed southwest toward Maydena and, beyond it, the gravel access road to the Styx Valley – prime logging country and the battleground of Forestry Tasmania versus the Wilderness Society and other conservation groups. Along the Styx Valley road, we spotted messages on defaced signs supporting both camps; the one shown on the right below was located at the entrance to Big Tree Reserve, a small parcel of land set aside by Forestry Tasmania.

Anti-Logging Graffiti (© Magi Nams)

Anti-Green Stickers (© Magi Nams)

Within the reserve, we learned from an interpretive sign that swamp gums live to be around 400 years old and that their extraordinary height and girth are due to the high rainfall (1000-1500 millemetres per year) and rich soil nutrient availability characteristic of wet eucalyptus forest sites, as well as a lack of regular wildfires. We strolled past the Big Tree, a swamp gum which in 1957 was 98 metres tall, but which has since shrunk to 86 metres due to crown dieback and storm damage. The reserve also protected the Bigger Tree, (87 metres). As we approached its base, we noticed a cameraman filming a blonde woman standing next to the giant swamp gum. Both openly friendly, they informed us that they were a Swedish film crew documenting the giant trees.

Swedish Film Crew in Big Tree Reserve (© Vilis Nams)

From the Forestry Tasmania reserve, with its large promotional sign, beautifully maintained paths, and artistically-designed viewing area facing the Bigger Tree, we drove 600 metres farther down the gravel road, and then 800 metres up Waterfall Creek Road, at which point we parked on a grown-over logging road and crossed the gravel to a couple of pink flagging tape ribbons indicating the start of the Tolkien Track. Dark and mysterious, narrow and rough, it was the least developed track we had hiked in Tasmania and granted us access to the scene of a protest launched in 2004 to protect this section of forest abundant with the giant columns of swamp gums. We hiked past moss-cloaked tree ferns and a split-trunk gum nicknamed Fangorn, and on to Gandalf’s Staff, a knobby swamp gum on which protesters had erected a platform 65 metres above the ground.2 We saw no sign of it, but a wood and wire boardwalk still encircled the giant tree’s trunk. The protest was successful, halting the clear-felling of the giants at the site.

Here I am beside Gandalf’s Staff (©Vilis Nams)

We followed the track farther into the tree-fern cluttered forest to an ancient, hollow gum known as Cave Tree, and then to the forest’s edge, where the clear-cutting had been halted. A thick growth of shrubs softened the empty clearing, through which we hiked to the road on a trail nearly swallowed by regenerating vegetation.

Hoping to reach Fortescue Bay in Tasman National Park – where we had camped our first two nights in Tasmania – before dark, we left the Styx and its giant gums in late afternoon, heading for New Norfolk, then Hobart, and then the state’s southeast tip. We drove past raspberry fields at Westeray, grabbed a road supper of chicken rolls and mini fruit pies in New Norfolk, and soaked up the best country music program we’d ever heard, which carried us past cherry orchards and the broadening River Derwent, past Hobart and the Tasman Bridge arching over the river like a white brontosaur possessing an entire suite of pillar-like legs and a long, lowered neck onto which cars could drive. Pacific gulls floated above the causeway across Pitt Water, and the setting sun gilded farms and gums we passed en route to the Tasman Peninsula.

Darkness fell, and a half moon rose, casting silver light between the tall, slim eucalypts bordering that dusty gravel road to Tasman National Park and our haven for the night. We scanned the road for devils one last time, looking for stocky, black, big-headed shapes running – not hopping – across the gravel. Again, we saw none, but that drive with the love of my life in the moonlight on a road between slim trees soaring against the night was at least as great a reward.

Tassie Sunset (© Vilis Nams)

Today’s fauna: rufous-bellied pademelon, sulphur-crested cockatoos, laughing kookaburra, green rosellas, *yellow wattlebirds, Bassian thrush, pink robin, black swans, Pacific gulls. (*lifelist sighting)

Reference:

1. James Stewart and Margo Daly. 2008. The Rough Guide to Tasmania. Rough Guides, New York. p. 99; 2. Ibid, pp. 326.