Aussie Right Down to the Spare (© Magi Nams)

Brilliant sunlight lasered through the sheer curtains of our hotel room at 8 a.m., waking Vilis and me after only four hours of rest following fitful dozing on a flight that eventually departed from Townsville shortly after 11 p.m. and arrived at Tullamarine Airport outside of Melbourne at 2:53 a.m. “You’re brave to be wearing shorts,” the hotel shuttle bus driver commented when he collected us in the middle of the night, his remark referring to a night temperature strikingly cooler than that of Townsville.

Through the hotel windows, our morning view was one of parking lots and multi-laned highways that in the near distance gave way to grazing country. On the eastern horizon, dark ranges of hills and the downtown skyscrapers of Melbourne rose like disparate mirages above the earth.

Vilis collected a rental car, and following a hurried breakfast, we drove east on the Western Ring Road to its intersection with the Hume Freeway, the main traffic artery connecting Melbourne with its rival city of Sydney in New South Wales. We headed north and then east on the freeway, our target the town of Tallangatta and nearby sheep country, in particular the farm of Andrew and Glenda Bowran. It was on Riversdale, the Bowrans’ farm, that Linda van Bommel, a Ph.D. student supervised by Chris Johnson, would today radiocollar several sheep and guard dogs. Chris had arranged with Linda to have Vilis meet her at the farm, and I was along for the ride.

Rocky pastures edged the freeway, with dugouts or windmills and troughs providing water to sheep and black Angus cattle. Scattered lines of crooked gums bordered fields of grazing land, and gorse and Scotch broom – invasive shrubby legacies of English settlers wanting a taste of home – grew unfettered in road allowances along with native shrubs. As we neared Seymour, the gentle hills showed evidence of bushfires in the scorched trunks of gums sprouting new, vividly green growth.

Victoria Rangeland (© Magi Nams)

Overall, the landscape was strikingly different from that of the wooded floodplain and ranges of low peaks surrounding Townsville. Vast, tawny rangeland washed with dull emerald and tufted with eucalypts having leaves the colour of green olives stretched away to a distant horizon. The trunks of the gums curved, twisted, spiralled, or leaned near jumbles of pink-grey boulders, as though writhing up from sandy, pink-brown soil in some timeless embrace of land and sun. The trees grew taller and lusher than the ironbarks and poplar gums in the open savannah woodland surrounding Townsville. Some were multi-trunked with broad, spreading canopies of leaves glinting silvery green in the sunlight.

Koala Crossing (© Magi Nams)

We drove for hours through this landscape, the rangeland occasionally interrupted by a resting crop field, a vineyard, or a hayfield regularly peppered with round bales of fodder. Road signs warned of koala crossing areas, and I looked for koala shapes high in the canopies of roadside gums, even though I knew the small gum-leaf eaters would be resting during the day and virtually impossible to spot among the clusters of leaves. Conical, forested hills near Glenrowan brought to mind Major Mitchell, the colonial surveyor who cleared trees from summits to create trig points, and later climbed tall trees to use them as trig points when no other height was available.1 Rich green fields at Wangaratta spoke of irrigation in a dry land, and white cumulus clouds rode the sky like fluffs painted on a vast blue bowl, so much like the Canadian prairie clouds of my childhood.

Traveling through the Victorian heartland, we listened to country music, which suited the landscape, and Vilis mentioned a comment he’d heard at JCU to the effect that, if you’ve seen Queensland and Tasmania, you’ve seen the best parts of Australia; there’s nothing anywhere else. “I wonder what the residents of Victoria would say about that,” I mused. Frequent road signs warned us of the dangers of driving exhausted – a condition perhaps encouraged by the sameness of the surroundings. Open Your Eyes: Sleep Kills. Droopy Eyes? Powernap Now. The second of these accompanied a sign indicating a rest stop ahead.

We paused for a sub sandwich in Wodonga, a pretty town near Albury I wished we had more time to explore, and then drove southeast to Tallangatta alongside an arm of Lake Hume, a reservoir spiked with black, drowned trees and surrounded by rolling hills.

Lake Hume (© Vilis Nams©)

At 2 p.m., after driving past the lane for Riversdale twice, we found it and the farmyard and home of the Bowrans. Both hearty, down-to-earth types, Glenda and Andrew welcomed us with open friendliness and introduced their son Steve (younger son Leigh up with the sheep) and a grizzled character Mel, who would drive Vilis, Linda, and me up to the sheep pen in a Toyota Land Cruiser. Recovering from knee surgery, Andrew was unable to accompany us, and Glenda remained with him. A perceptive hostess, Glenda offered Vilis and me space in the house to change our clothes and heed the call of nature before heading off into the hills.

While the Land Cruiser clawed its way up into the high country above the farmyard, Vilis and I chatted with Linda, who is Dutch and has lived in Australia for 5 years, and with Mel. “This sure is a rocky pasture,” Vilis remarked, to which Mel replied, “Good sheep country.” Steve rode ahead on a dirt bike, with a rifle slung across his back and Jack, the kelpie, onboard behind him.

Riversdale Sheep Country (© Vilis Nams)

Steve Bowran and Jack (© Vilis Nams)

We learned from Mel that winter is the wet season in Victoria, when vehicles, including tractors, can get bogged down on the rough track we were driving, which crept around the shoulders of precipitous slopes and seemingly ever upward on the faces of steep inclines. Linda told us that she had a total of 8 collars, 4 for the Maremmas, which are an Italian breed of livestock guard dog, and 4 for sheep. Once in place on the experimental animals, the collars will automatically calculate and store data on the Maremmas’ and sheep’s locations, which Linda will use to try to determine exactly how the guard dogs’ presence causes such a dramatic decrease in predation on sheep by wild dogs.

Linda van Bommel Collaring a Maremma with Steve Bowran’s Help (© Vilis Nams)

At the sheep pens, we met Leigh, and Steve called in the Maremmas and introduced us to Bindi, Mudgee, and Gonga, and later to Ringo, who was apparently the hardest worker of the quartet of guard dogs. Steve explained that the Maremmas perch up on the hilltops and watch for any enemies. If they spot wild dogs, they run down and muster the sheep and guard them. They move the sheep to the top of the hill and hold them there, then find the wild dogs and escort them off the property. Vilis and I quickly picked up on the fact that the Bowrans speak of Maremmas and dogs, the latter meaning wild dogs, but they don’t mention dingoes. As far as they’re concerned, there’s no pure dingo blood left in the animals that prey on their lambs. For about 6 years, Steve said they would spend 5 hours up on the hills every morning shooting dogs, after which they put in a full day’s work before returning to the hills again in the evening.

The Bowrans’ home farm encompasses 3000 acres, but with Steve’s and Leigh’s adjoining properties added on, the total reaches 5000 acres. Together, the properties support 2000 merino sheep, which are raised for their wool, as well as cattle. With about 600 breeding ewes, the Bowrans got hammered for those 6 years Steve had mentioned, losing nearly all of their lambs to predators and almost going out of business. Then they brought in the Maremmas, and the guard dogs turned darkness into light, protecting the sheep and saving the business. Steve explained that they brought each of the Maremmas home at 8 weeks of age and trained it for 6 or 7 months, first with a small paddock of sheep down near the yard. They gradually increased the number of sheep and size of paddock until finally bringing the guard dog up into the hills, where it assumed its job of keeping watch over the far-ranging sheep, while once in a while slipping down to the sheep pen to grab a bite to eat from the bags of kibble left open in a shed.

Linda showed me the thick, wide canvas collars for the Maremmas, each with a GPS unit, which logs locations, and a VHF transmitter, so she can find the dogs in the field by using an antenna and receiver. She collared Gonga first, and then gave decorations to Bindi and Mudgee, but Ringo hadn’t yet made his appearance. In Steve’s familiar and calming presence, the dogs were docile and cooperative, the collaring progressing much faster than Linda had expected.

Preparing to Collar a Sheep (© Vilis Nams)

After collaring the 3 dogs, Linda worked with Steve and Leigh to collar 2 sheep in each of 2 mobs held in separate pens. To someone who knows nothing about working with sheep, it came as a surprise to watch Steve stride in among the milling bodies and simply grab one, hook his arm around its neck, and haul it back onto its haunches, at which apparent signal, the sheep became motionless and put up no resistance. He later explained that the sheep are accustomed to being handled for shearing or to receive medication. When the gates were opened and Jack, the 14-year-old kelpie, went to work moving the sheep out, the Merinos leaped and kicked in the air in a dusty rush through the opening.

Collared Ewe (© Vilis Nams)

Mel spotted Ringo resting in the shade by the pen, and he, too, received a collar. Then Steve and Jack on the dirt bike led the way to the top of the hill for a view out over Riversdale. It was all rugged, green hills pimpled with grey rocks and tufted with gums that, on distant hills, coalesced into dark forests. We spotted 3 wedgies (wedge-tailed eagles) soaring high above the hills, and talked of white cockies and black cockies (cockatoos) and bushfires that swept through the hills in 2003. Steve pointed out the home farm, with its silver-roofed shearing shed, and his and Leigh’s adjacent properties, and generously offered to show us even more of the farm tomorrow morning, if we wanted.

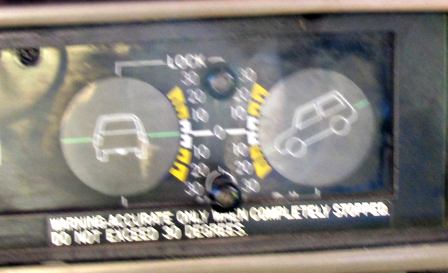

When we headed downhill, the clinometer in the Land Cruiser indicated just how steep the hills were. Back in the farmyard, we joined the Bowrans for refreshments on a shady patio, and Glenda marked out a more scenic route back to Melbourne on our roadmap. Vilis and I finally said our farewells almost 4 hours after arriving. I took images with me – roll-your-own cigarettes, dust billowing around leaping sheep, tough young men oozing self-reliance, and hospitality– incredible, heart-warming hospitality.

Hilltop View of Riversdale (© Vilis Nams)

Clinometer in Jolting Land Cruiser (© Vilis Nams)

More than a little fatigued by a disjointed night and intense day, we returned to Tallangatta and booked into a motor inn for the night. Supper in the Tallangatta Hotel was fresh, local trout for me and a basket of seafood for Vilis, our plates also piled high with chips and salad or cooked veggies. While waiting for my meal to arrive, I wandered through the dining room of that real, old-fashioned country pub hotel and stared at old black and white photographs of bullock teams from some unknown date, and of the local hunt club mounted and jacketed, in 1955. A colour photo from 1959 showed the old town flooded by the dam, with the tops of buildings and upper branches of trees protruding from the water. When at last Vilis and I crashed into bed, we realized that, for the first time since our arrival in Australia, the evening air entering the screened window was cool.

Reference:

1. Ashley Hay. Gum: the story of eucalypts and their champions. 2002. Duffy & Snellgrove, Sydney, pp. 45, 62.