Licuala Fan-leaved Palm Forest (© Magi Nams)

In the darkness of 5 a.m., Vilis and I rose from our bed, packed gear for an outing, and drove north from Townsville on the Bruce Highway, our destination the cassowary hotspot centred on Mission Beach, east of Tully. Three hours after departing Townsville, we arrived at Licuala State Forest Park, where Licuala fan-leaved palms soared above the ground, bearing split-leaved fans that tossed green circles against the sky. Remnants of a once-expansive lowland rainforest, the Licuala palms, with their shallow roots and flexible trunks, are adapted for life in the Wet Tropics’ waterlogged soils and cyclone-prone climate.1 On the Rainforest Circuit within the park, they formed the dominant vegetation, although thick-boled non-palms rose among them.

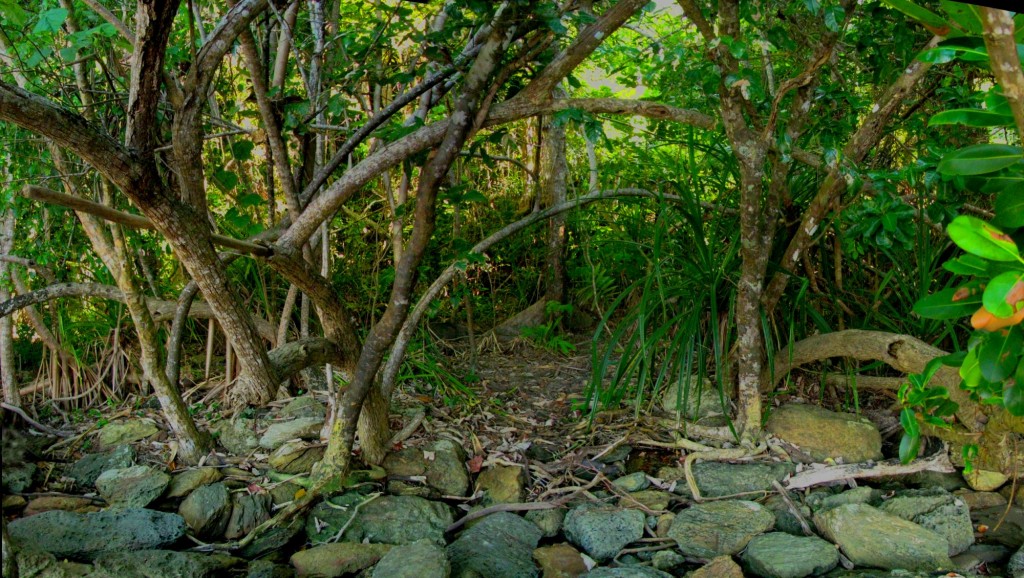

Beneath the Licuala palms, the forest understory was a wild tangle of pinnate-leaved palms, barbed wait-a-while vines that snagged our clothing, and urchin-fruited pandanus with toothed, strap-like leaves that rattled when you touched them and tore your flesh if you rubbed them the wrong way. Ferns and native ginger threw arcing fronds into the open air above the path, and trunks of trees snared by strangler figs and leafy vines looked as though they’d been taken prisoner. The understory vegetation was so dense that, for some sections of track, we seemed to be walking between leafy, reaching walls.

Here we are on Rainforest Circuit in Licuala State Forest Park (© Vilis Nams)

The orange fruits of the Licuala palm are a preferred food of southern cassowaries, who had left an abundance of sign on the track. Large piles of cassowary scats adorned the path, some old, some new, some with seeds sprouting in their midst. Other favoured foods of the cassowary include the fruits of brown gardenia, cassowary satinash, solitaire palm, umbrella tree, cassowary pine, and cluster fig, although the large frugivores consume fruits and berries of more than 230 species of rainforest plants.1 The bird’s gentle digestive system allows the seeds to pass through undamaged, and thus, the cassowary is a highly effective dispersal agent for rainforest plants, some of which rely on it exclusively.1

Cassowary Scat (© Magi Nams)

Rainforest Trees Sprouted from Cassowary-dispersed Seeds (© Vilis Nams)

Despite the large number of scats on Rainforest Circuit and Children’s Circuit (and the admonition to not feed the cassowaries, and the fenced picnic area having a gate to keep cassowaries out), we saw not a single one of the large, flightless birds. Still, we were left with no doubts that cassowaries really were out there, stepping through the dense rainforest, feeding on its fruits, and dispersing their seeds. Determined to find one, we hiked another trail called the Rainforest Walk for two hours, again encountering numerous cassowary scats and a bevy of smaller rainforest birds – eastern whipbird, rufous fantail, black butcherbird, little shrike-thrush, spectacled monarch, yellow-spotted honeyeater, Macleay’s honeyeater, and the wompoo fruit-dove, the last gargling its throaty “wwrom-pooo” over the forest.

Southern Cassowary Footprint (© Vilis Nams)

And then, we saw one. After photographing a scat, Vilis glanced back along the trail and spotted a southern cassowary – one of Australia’s iconic birds. An adult with a prominent casque atop its head, the cassowary sauntered peacefully along the track some distance behind us, before stepping into the rainforest. “It was huge!” Vilis whispered as we retraced our steps, hoping to spot the cassowary in order to photograph it. We found its tracks in the greasy mud of the trail, but the bird itself had disappeared.

Boyd’s Forest Dragon (© Vilis Nams)

Leaving Licuala State Forest Park, we drove to the Lacey Creek Circuit in nearby Tam O’Shanter National Park, where again we dodged numerous cassowary scats on the trail, but saw no cassowaries to photograph. I did spot an impressively-spiked Boyd’s forest dragon – a reptile I’d been yearning to see – that bounded through forest litter and leapt up onto a tree trunk, where the 60-centimetre lizard froze into stillness, allowing Vilis to capture its image.

In a last effort to find a cassowary to photograph, we drove north from the Mission Beach area to Etty Bay just south of Moresby Range National Park near Innisfail, where, according to staff at the Tully information centre, cassowaries abandon the rainforest in late afternoon to walk the beach. A little sceptical of this (“Why would cassowaries come onto a beach?” Vilis asked), we nonetheless spread out our beach towels on the sand of Etty Bay’s highly attractive and well-used beach in the hope of observing a southern cassowary.

Wanting to explore, I strolled the beach to its southern end, noting the rainforest abutting the sand and what appeared to be trampled ‘paths’ at the forest edge.

Etty Bay Rainforest Edge Cassowary Habitat (© Vilis Nams)

Southern Cassowary (© Vilis Nams)

I also spotted a cassowary resting in the shade of a low tree growing on the beach, the bird – which was obviously habituated to the presence of humans – positioned within a few metres of a couple of beach-goers seated in lawn chairs. Intrigued, Vilis and I watched as the cassowary, an immature bird with a small helmet or casque, left its resting place and placidly strolled the beach. Cloaked in its thick plumage of coarse feathers intended to shed water and offer portection from the rainforest’s barbs and spikes,2 the cassowary walked right past our towels, stared at a young woman working at a laptop computer at a picnic table, poked its beak into debris tossed up by the tide, and strolled over the sand, pausing to gaze at swimmers frolicking in warm, green waves.

Southern Cassowary at Etty Bay (© Vilis Nams)

Within Australia, southern cassowaries occur only in wet tropical rainforests of North Queensland3 and are a protected species. They also live in Papua New Guinea, where two additional species of cassowaries occur.2 Along with Australia’s emu and the African ostrich (which was introduced to Australia for farming and may now exist as feral populations in South Australia), the cassowaries belong to the elite group of flightless birds known as ratites, which include the world’s largest living birds.2,3 The southern cassowary is Australia’s second largest native bird after the emu and occupies a far more restricted geographical range than does its fellow member of the family Casuariidae, the emu occurring throughout most of Australia with the exception of heavliy settled areas, extreme desert, and Tasmania, from which it was exterminated.3 I count myself extremely fortunate to have seen cassowaries in the wild and can only hope I’ll be as fortunate with that other native Australian ratite, the emu, which I have not yet encountered in its natural habitat. For that, I need to go inland, onto the dry expanses of the outback. Wish me success.

Southern Cassowary at Etty Bay (© Vilis Nams)

Southern Cassowary (© Vilis Nams)

Today’s fauna: black kites, Australian magpie, whistling kite, sulphur-crested cockatoo, straw-necked ibises, masked lapwings, anhinga, mynas, magpie-larks, willie wagtail, pheasant coucal, eastern whipbird, rufous fantail, *black butcherbird, little shrike-thrushes, yellow-spotted honeyeater, spectacled monarch, Macleay’s honeyeater, *southern cassowaries, wompoo fruit-doves. Also observed blue triangle butterflies and *Boyd’s forest dragon. (*denotes lifelist sighting)

References:

1. Interpretive signs at Licuala State Forest Park and Lacey Creek Circuit, Tam O’Shanter National Park.

2. Graham Pizzey and Frank Knight. The Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. 1997. Angus & Robertson, Sydney, p. 521.; 3. Ibid, p. 18.