Alligator Creek (© Vilis Nams)

Allied Rock Wallaby (© Janis Nams)

Nearly five months after Vilis and I bushwalked the first few kilometres of Alligator Creek Track under blistering sun in early February, vowing we would return and complete the hike in winter, we, along with Janis, returned this morning. At the trailhead in the Alligator Creek campground located about 25 kilometres south of Townsville in Bowling Green Bay National Park, a cool, refreshing breeze swept over us, promising far more comfortable hiking conditions than on our summer attempt. We spotted several allied rock wallabies grazing on the mowed grass of the campground and picnic area, and listened to Australia’s dawn chorus of birds singing from the campground trees.

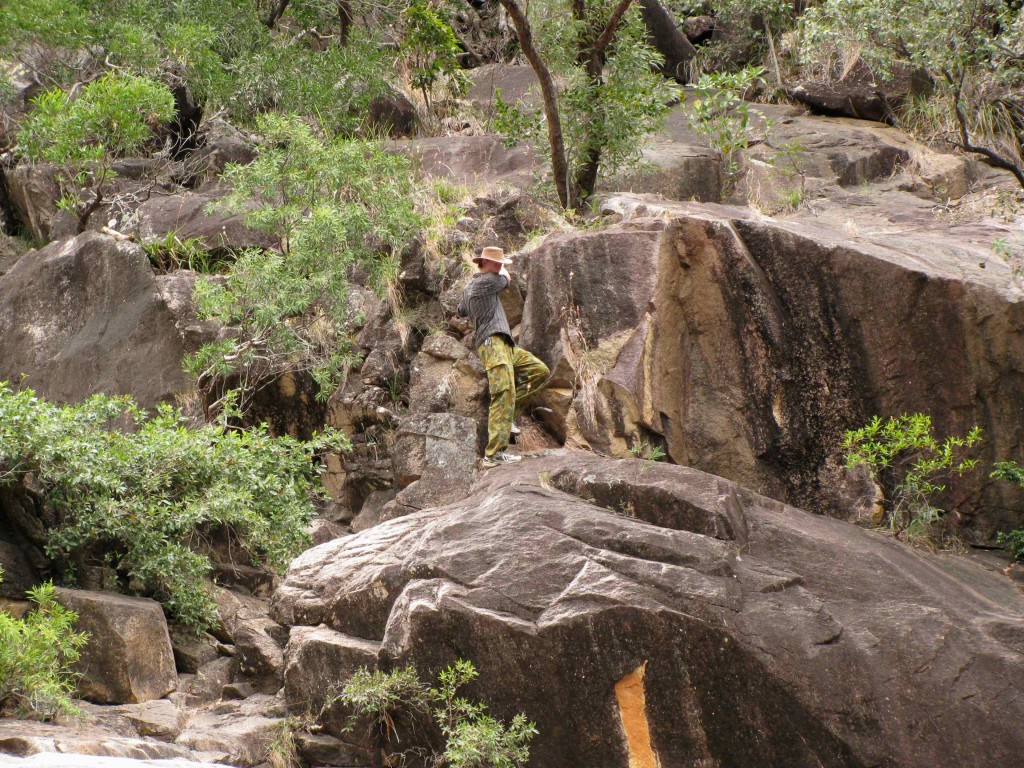

Janis on Alligator Creek Track (© Vilis Nams)

The 8.5-kilometre track to Alligator Falls led us through a mix of tropical savannah woodland, sections of mowed grassland beneath 66,000-volt steel transmission towers, and vine thicket, a type of dry rainforest. The terrain was mostly flat or gently undulating, with only a few steep inclines. Sections of boulder field in the vine thickets offered Vilis the opportunity to indulge in his love for rainforest vines. We crossed several dry creekbeds that were no doubt rushing torrents during the Wet, and rock-hopped our way across Cockatoo Creek and a trio of crossings of Alligator Creek.

Here Janis and I are crossing Cockatoo Creek (© Vilis Nams)

Vilis and Vine (© Magi Nams)

Birds seemed to be everywhere. In the cycad-speckled woodland, a little shrike-thrush probed for insects in the crotches of a gnarled poplar gum, and a spangled drongo glistened black and green atop a dead tree, its red eye lit by the sun. Red-browed finches flocked through shrubs and trees adjacent to the powerline grassland, and a young red-tailed black-cockatoo emitted hissing calls from a tall tree. Scaly-breasted lorikeets foraged in tall gums, dusky honeyeaters hung from branches of riparian trees, and a trio of songbirds I’d never seen before – spectacled monarch, rufous fantail, white-browed robin – flitted about within a few metres of each other in a strip of vine thicket.

More rock wallabies foraged in the powerline grassland, and Vilis chased a snake far enough to get a good look at its black dorsal surface and yellowish-red lower sides, which enabled me to identify it as a red-bellied black snake, one of Australia’s toxic celebrities. Small yellow butterflies called grass-yellows were so abundant in the open woodland that they resembled little, lemon-coloured flowers fluttering in the breeze, while a stunningly beautiful Ulysses swallowtail blinked like a blue jewel floating erratically above Alligator Creek before alighting on a gum twig, folding its wings together, and disappearing into the foliage.

Dense Vines in Vine Thicket (© Vilis Nams)

Alligator Falls (© Vilis Nams)

Our arrival at Alligator Falls came abruptly, the spill of water revealed through an opening in the vine thicket densely vegetated with trees, shrubs and vines bordering the track. White water tumbled, dripped, and slid in smooth, scalloped sheets down the bulges and steps of a gigantic, sloped wall of pink granite encrusted with black lichen. At the base of the falls, the slide of the water was gentle and mesmerizing, like a moving layer of white lace continually slipping into a black pool. I tried to imagine what the falls had looked like during the pounding fury of the monsoonal lows, and on mentioning this to Vilis, his response was that the problem would have been getting to the falls – past the flood-prone trailhead access road and all those creek crossings – to see it.

Janis Descending Alligator Falls Granite Wall (© Vilis Nams)

Janis took one look at the rising granite slope and said, “I don’t know about you guys, but I’m going to climb the waterfall.” He crossed the narrow creek at the base of the falls by jumping over it from a massive boulder, and proceeded to scramble his way up the edge of the wall until he reached a ledge high above Vilis and me. He would have climbed higher, he told us after his descent, but he’d thought I’d be worried about his safety.

Cloud began building overhead, with epehmeral drizzle spitting down onto us as we commenced the return hike to the campground. Beyond the vine thicket near the falls, we again encountered horse dung on the track, sign left by brumbies (feral horses) inhabiting the national park. The sporadic thundering sound we’d heard while hiking to the falls, which we’d speculated was caused by the military practising with heavy artillery in the training area at the base of Mount Stuart, had ceased, and the early afternoon chorus of birdsong was soft. I spotted more scaly-breasted lorikeets feeding high in gum trees, and waxed eloquent over subtle shades of winter (which Vilis and Janis didn’t really see) in the open woodland.

Tropical Savannah Woodland Winter Colours (© Magi Nams)

On our drive home, yet another glimpse into Australia’s diversity of fauna came in the form of a dingo (or wild dog, depending on your definition) feeding on road kill in a ditch near Townsville. As with the bustards I saw at Ross River Dam last Sunday, this sighting was unexpected, my imagination setting dingoes in forests and grasslands and, as in Western Australia, in deserts. However, they, like the bustards, range over most of this continent,1 including city outskirts, it would appear.

Reference:

1. Peter Menkhorst and Frank Knight. A Field Guide to the Mammals of Australia, 2nd edition. 2004. Oxford University Press, Victoria. p. 210.

Today’s birds: Torresian crow, blue-faced honeyeater, magpie-larks, black kites, whistling kite, sulphur-crested cockatoo, little shrike-thrush, spangled drongo, dusky honeyeaters, white-throated honeyeater, yellow honeyeater, red-browed finches, peaceful doves, bar-shouldered dove, *spectacled monarch, *white-browed robin, *rufous fantail, red-tailed black-cockatoos, leaden flycatchers, grey fantails, white-winged triller, scaly-breasted lorikeets, figbirds, masked lapwings, rock doves, mynas. Also observed allied rock and agile wallabies, red-bellied black snake, grass yellows and Ulysses swallowtail, and dingo. (*denotes lifelist sighting)