Pandanus Palm at Tyto Wetlands (© Vilis Nams)

At first light, Vilis and I headed north on the Bruce Highway for a spot of early morning birding at Ingham’s Tyto Wetlands, after which we continued north to Tully for a tour of the Tully Sugar mill during the afternoon. Brilliant blue sky and a fresh breeze offered good weather for both pursuits, in contrast to last week’s rain in the Tully area that resulted in the cancellation of mill tours because it was too wet for harvesters to access paddocks of cane.

In the Tyto Wetlands, crimson finches flew like small flames spurting among the grasses. Willie wagtails hunted insects on lily pads, swishing their long, lovely tails back and forth as though dancing a wetland rumba on oval dance floors scattered over the surface of the water. Comb-crested jacanas strode across floating leaves on long-toed feet, earning their nickname of water-walking ‘Jesus birds.’ Brush cuckoos sang solemn, descending ladders of “fear-fear-fear-fear..” while a male yellow-bellied sunbird drank nectar from treetop flowers, his iridescent throat and chest a shimmering black bib overhanging his brilliant yellow shirt.

After nearly three hours of birding, we replenished our energy reserves with hot meat pies and custard-filled éclairs from Ran’s Cakes and Pies in Ingham (a great place to indulge in a post-birding snack), after which we traveled on to Tully. The sugar mill was surprisingly large, with an exterior of corrugated metal, and stacks belching steam and pale grey smoke into the air. Our tour guide Rebecca outfitted us with safety helmets, protective goggles, and earplugs before leading us into the mill.

Tully Sugar Mill, Tully, Queensland (© Vilis Nams)

Cane Train at Tully Sugar Mill (© Vilis Nams)

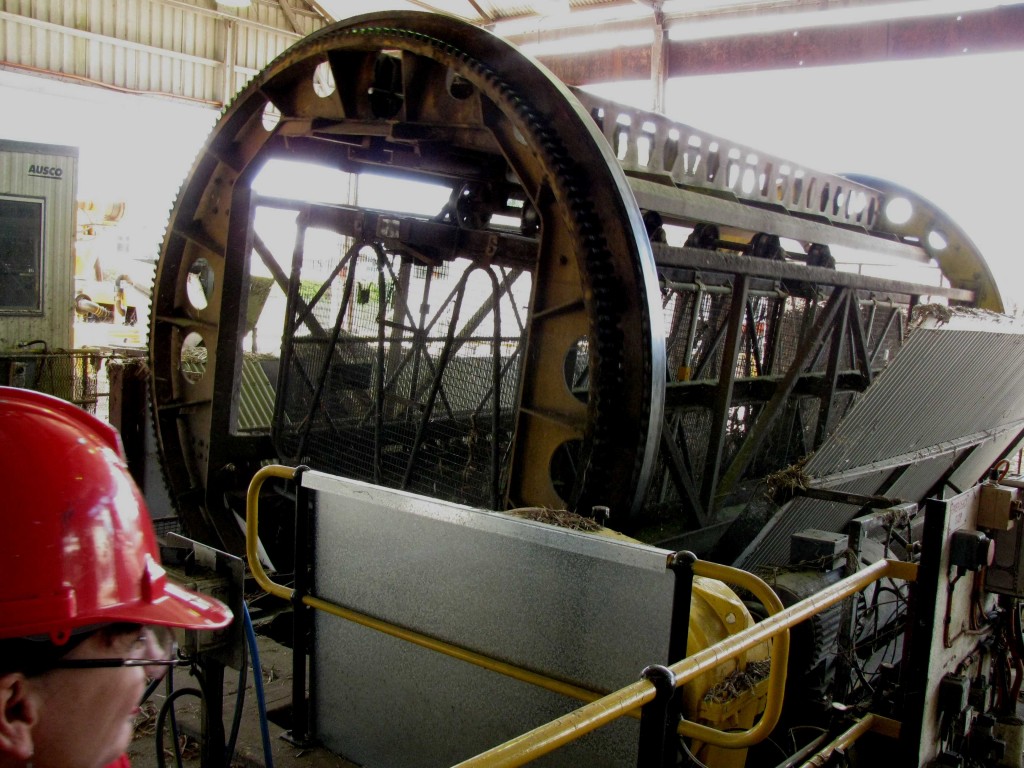

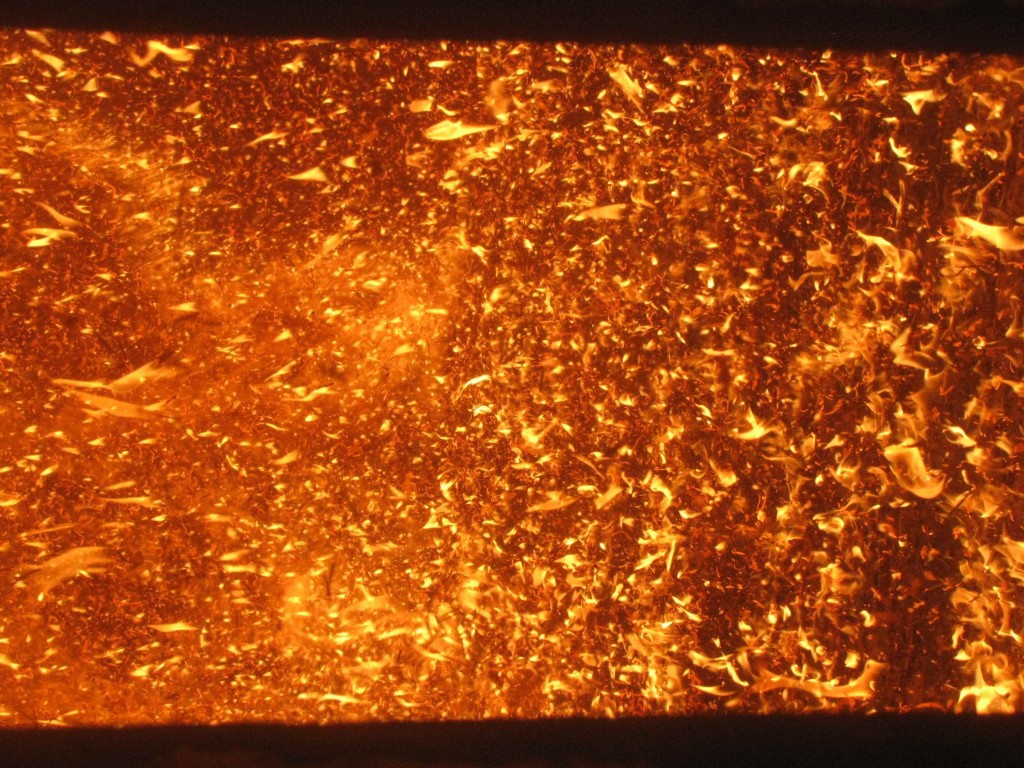

We followed train bins filled with cane as they rolled into the mill and were weighed, then flipped 360° to empty their contents onto a conveyor belt which carried the cane to a shredder. Shredded cane then passed into the first of a quintet of mills or crushers that extracted cane juice, leaving a dry, fibrous residue called bagasse. Extracted cane juice continued on to the next step – boiling and liming to clarify the juice and remove soil particles. The bagasse traveled by conveyor belt to a huge boiler plant, where it was burned to vaporize water into steam to power the mill and generate electricity, with excess electricity being sold to the power company.

Emptying Cane Bin (© Vilis Nams)

Burning Bagasse in Boiler Plant (© Vilis Nams)

Cane on Conveyor to Shredder (© Vilis Nams)

The interior of the mill was loud and flecked with cane dust. Steam wafted from floor grates or machinery, and occasional drops of water or syrup fell through the air. Thick, stomach-unsettling odors pervaded the interior, and handrails carried a sticky sheen.

Tully Sugar Mill Interior (© Vilis Nams)

Rebecca showed us the amber-coloured cane juice bubbling in the clarifier and allowed us to peer through a window into the red-hot, glowing interior of the boiler plant. She pointed out huge evaporators used to concentrate the boiled juice, after which it’s seeded with powder-fine sugar crystals to initiate crystallization. After seeding, evaporation continues until the crystals reach a millimetre in size, at which time they’re part of a sticky, dark-brown mass of sugar and molasses called massecuite. Rebecca led us to a row of centrifuges, where the tour group of twelve gazed into huge, spinning tubs that threw sugar crystals against the tub walls while allowing molasses to drain out, rather like the spin cycle of a washing machine, as Rebeccca pointed out.

Centrifuge Separating Sugar from Molasses (© Vilis Nams)

From the centrifuges, the washed sugar crystals were transported on conveyor belts to be dried and stored. Rebecca dipped a handful of hot sugar from a belt for us to taste.

Tully Raw Sugar (© Magi Nams)

.

All of the sugar Tully Sugar Ltd. produces is trucked to Mourilyan Harbour near Innisfail, loaded onto ships, and exported to markets around the world. The mill crushes 2,000,000 tonnes of cane a year over a season of 21 weeks (June to mid-November), resulting in 100,000 tonnes of cane crushed per day. The average sugar content of the cane processed is 12.87%, and the mill is projected to produce 250,000 tonnes of raw sugar and 50,000 tonnes of molasses this year.1

Tour Guide Rebecca and Vilis at Tully Sugar Ltd.

In addition to producing sugar, molasses, and excess electricity, the mill also produces milling by-products useful to cane farmers. We watched a mill worker load a truck with ‘mill mud,’ a black, nutrient-rich sludge consisting of the impurities extracted during the boiling and clarification of the cane juice. The mill sells the ‘mud’ to cane farmers to dress their cane paddocks. Ash residue remaining after the bagasse is burned is given to farmers to apply to fallow cane fields. With all its recycling initiatives and minimal smoke emissions (8%, produced in only one stack)2 Tully Sugar Limited is recognized not only for its high quality sugar, but also as a world leader in green technology.

Today’s fauna: Brahminy kite, black kites, masked lapwings, mynas, anhingas, willie wagtails, agile wallabies, Australian white ibises, brown honeyeaters, crimson finches, magpie-larks, little corellas, great egrets, pheasant coucal, peaceful doves, yellow honeyeaters, rufous whistler, yellow-bellied sunbird, brush cuckoos, spangled drongo, golden-headed cisticolas, bar-shouldered doves,*tawny grassbird, reed warbler, forest kingfishers, rainbow bee-eaters, comb-crested jacanas, Pacific black ducks, red-backed fairy-wrens, olive-backed oriole, varied triller, rainbow lorikeets, welcome swallows, black-fronted dotterels,*hoary-headed grebes, white-breasted woodswallows, little shrike-thrushes, straw-necked ibises, intermediate egret, cattle egrets. (*indicates lifelist sighting)

References:

1. All data from Tully Sugar Limited Operational Statistics 2010, Tour handout.

2. Data from Tully Sugar Limited tour guide Rebecca.