Oak Valley Hilltop View, with Lake Ross in Background (© Magi Nams)

Chased from the slopes above Oak Valley by drenching sheets of rain on January 30, Vilis and I returned to the nature reserve this morning and spent nearly 3 hours hiking its hills. When we arrived at the picnic site and bird-watching shelter beyond the end of Thunderbolt Drive, it was immediately apparent that the groundcover of grasses in the open savannah woodland was much thicker and taller than it had been three weeks ago, no doubt nourished by the frequent rains the Townsville area has received in the interim. Again, water from seepage down the nearby hills ran over the ground surface on level areas adjacent to Sachs Creek.

Wild Hibiscus, Oak Valley Hills (© Vilis Nams)

We hiked up a rock-strewn slope to a ridge, passing patches of wild red hibiscus growing on rock outcrops and spooking a wallaby from its cover of shrubs. Vines bearing dense foliage of vivid green leaves entangled trees and shrubs, and grasses brushed against my waist and shoulders as we panted and sweated uphill through the humid air.

The ridge swept upward to the southern slope of a high hill, which, after we scrambled to its summit, offered us a 360° view. To the north, Magnetic Island was a slim collection of hazy hills on the blue of Cleveland Bay, while to the south, Ross Lake lay spread across its catchment basin. The roofs of houses within the Oak Valley rural suburb glinted silver among stands of trees between the lake and reserve, and a few secluded homes perched high on the summits of low hills overlooking Sachs Creek. To the east, Mount Elliot rose dark and brooding over Bowling Green Bay National Park, while to the west, boulder-strewn, conical hills bordered Sachs Creek, with the richly forested peaks of the Hervey Range far in the distance beyond the open woodland we could see past the hills.

Oak Valley Slopes (© Magi Nams)

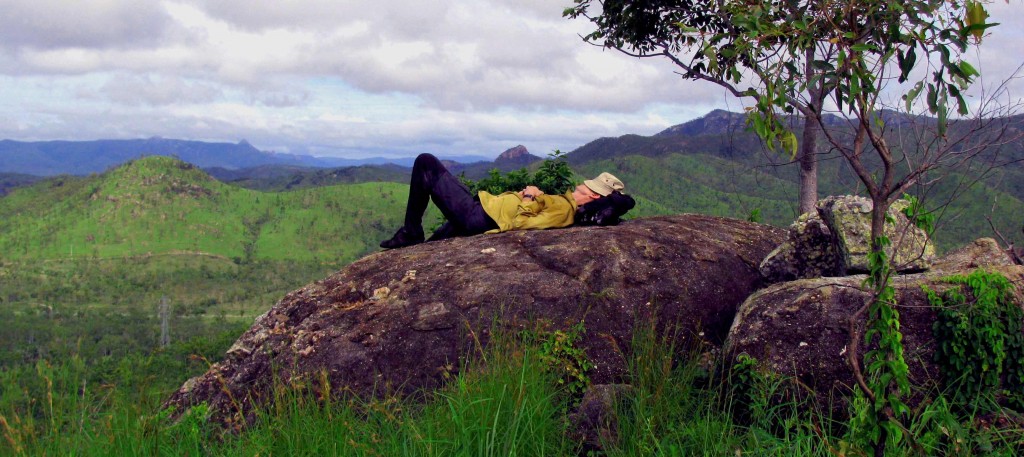

Vilis and Oak Valley Hilltop View (© Magi Nams)

We rested on a boulder outcrop among stunted poplar gums and other eucalypts, using our umbrellas to provide shade while we peeled and ate oranges. Far below us, the riparian forest bordering Sachs Creek formed a snaking curve of distinctly denser and darker vegetation than that of the savannah woodland. From our viewpoint, the open woodland appeared deceptively easy to traverse, with its lush, green grasses hiding all the loose, ankle-rolling stones and rocks scattered across the ground surface.

Cane Toad (© Vilis Nams)

From our rest stop, we linked up with a track that descended from the hilltop, part of which we had tramped on our previous Oak Valley excursion. We came across a decomposing macropod carcass, and – like a scene from some macabre movie – watched two cane toads hop out from under the decaying ribcage while flies swarmed through the air. Farther along the track, clear-winged swallowtails and small, brilliantly yellow butterflies called small grass-yellows flitted among blue, purple, and yellow wildflowers. When one of the grass yellows landed on a leaf, it could have been mistaken for a flower itself.

The track, which was much easier to hike than the surrounding hillsides (on it, you could see the rocks and stones that were about to roll under your feet), led us westward and downward to the wet meadow at the base of the hills. As we squelched along beside a rutted road filled with water, something thrashed about in the thick, water-loving vegetation near my feet. “Snake!” I shouted to Vilis, who was walking behind me. “Black. Really fast!” The snake, which had been completely hidden from view, writhed away from me, its glossy black back undulating through and over the plant cover, allowing me to estimate its length at a metre and a half or more, and its body diameter at a couple of inches. Then it was gone, and I was left wondering if I had encountered one of Australia’s toxic celebrities.

In contrast to the quiet of the open woodland, the forest alongside Sachs Creek was vibrant with avian sound and movement. Rainbow lorikeets fed noisily in eucalypts on the far side of the creek, lemon-bellied flycatchers perched atop a tree and repeatedly burst into upward flight in pursuit of insects, and a white-throated honeyeater and white-bellied cuckoo-shrike winged secretively from one tree canopy to another. I scanned the trees for endangered black-throated finches until a wild wind blasted rain into the picnic area and sent us homeward.

In the car, I looked through my reptile guide and came up with two possibilities for the identity of the snake I had seen: a water python or a red-bellied black snake, both of which occur in the Townsville area. In the end, I went for the red-bellied black because of the snake’s high-gloss black back, relatively slender (in comparison with a python) body diameter, speed of movement, and the fact that I had encountered it during the day, when red-bellied blacks are active, rather than at night, when water pythons are generally active. I didn’t see the underside of the snake at all, so couldn’t use the black snake’s red belly versus the python’s’ yellow belly as a distinguishing characteristic. So, I might be wrong, but if not, then yes, I did encounter one of Australia’s toxic celebrities.